In December, after a couple of months of health improvement, I got quite suddenly much worse, ending up severely ill for 5-10 days, feeling like I was more than halfway to dead This blog is about that experience. I am writing this in early January, recovered from the worst of it, though still very limited and fragile.

Opening Metaphor

Imagine there’s a lift on the tenth floor of a building. There is a safety mechanism to catch the lift if it falls, which can stop the lift at different floors as it falls past them, but it is single-use and damages the lift. There is no monitoring mechanism to know how quickly or far it is falling. Suddenly, the cable mechanism breaks and the lift starts to fall. The lift controller has to decide which crash barrier to place. They could deploy level 8 – but the lift may already have gone past it, so it did nothing. They could deploy at level 2 – which (almost) guarantees that the lift won’t hit the bottom, but the lift will have fallen 8 storeys. They could deploy at level 7, listen for the crash, and if they don’t hear it try level 3.

That metaphor is my attempt to show one of the difficulties of trying to manage the condition.

Background Information about PACS

Some background about the condition. One of the difficulties with post-acute covid syndrome* (PACS, aka long covid, post-acute sequelae of COVID-19, post-covid syndrome) is that there is an invisible and unknown limit of how much you can do. This includes physical activity, but also mental and emotional exertion and stress. The biological cause of this limit, I’m not sure is known yet. There are only so many steps you can take in a day, only so much thinking energy available, so much stress your body can tolerate. Usually, by the time we know we’ve crossed the line, it’s already too late. Were I to exercise, by the time I start to feel tired, my cells running out of energy, I’ve already overdone it – whatever is going on with mitochondrial dysfunction means that there will be problems. I have had times where I felt totally fine during the exercise (this season usually a 2-3km walk) and afterwards seemed totally fine, but it turned out the next day I had overdone it. Sometimes we can feel bad immediately afterwards, but the ‘post-exertional malaise’ effect typically hits 12-36 hours afterwards.

*Though the condition includes many related sub-conditions. Here I am talking primarily about the fatigue and autonomic nervous system dysfunction which includes problems with mitochondrial dysfunction, blood vessels not working properly, and acute ANS dysfunction.

Overdoing it causes a ‘crash’ of some variety, either immediately or with the 12-36 hour time lag. This can involve a range of symptoms. Usually, the autonomic nervous system gets into a stressed state, there is fatigue, headaches, and negative emotions. In the short-term, it’s unpleasant. But in the medium and long term, it means that one’s general condition can get worse. Living in a boom-and-bust cycle of overdoing it, paying the price for 1-3 days, recovering, then going again, means that one can get worse over time – as has happened to me a few times. It’s not like a food intolerance, where you could eat pizza and ice cream if you really wanted and pay for it for a couple of days with no risk of any problems beyond that. It is not a condition where pushing through makes any sense.

The big danger is becoming bedbound. If someone keeps getting worse, their thresholds can fall so low that even the daily basics are too much: walking to the toilet, washing, basic brain activity and communication, eating and digesting can all be a problem. People get stuck here because basic survival involves a biological deficit which cannot be escaped – like a gravity well or trying to empty out a boat with a leak. There are examples of people like this online, if you would like to look for it. The science communicator Dianna Cowern, YouTube channel ‘Physics Girl’, is one example with documentation.

This isn’t new with Covid-19 either: ME/CFS and post-viral fatigue has been around for a long time. A friend who studied the Spanish Flu told me that the same thing happened to many people after that pandemic, with many being sent to live in asylums.

There’s also the risk of being ill enough that while not bedbound, independent living and earning enough money to live off isn’t possible. Avoiding this was my priority: ensuring that my health is always trending in a positive direction has been vital.

The condition is still not well understood. Many of the pathologies are known and being researched: the ANS doesn’t work properly, which impairs blood flow around the body; mitochondria in the cells don’t function properly, limiting energy production; blood vessels are damaged and inflamed, impairing the micro-level exchange with cells; the body or particular areas become inflamed; there can be autoimmune responses; and more. Why exactly this happens, I don’t know, and I don’t think researchers have discovered yet. There are a few theories going, but none seem to fully explain or cover all of the issues. But, for whatever reason, when we do too much, it gets into a negative cycle where blood vessels are impaired, mitochondria are damaged and dysfunctional, and the ANS is dysregulated and more fragile. We feel fatigued, stressed, headaches, etc, because, biologically, basic bodily functions are not working properly.

Managing the condition is about figuring out a version of ‘pacing’ – working out what can safely be done each day without crashing. As well as avoiding crashes and getting more ill, it means that the body can stay in a restful state and (hopefully) undergo a healing process. I had been on a gradual healing trend since my last severe regression in last May, 12 months after I first got covid. A few months ago, in September, I could walk about a kilometre at careful speed, work on my laptop for 4-6 hours each day, and do about 1 hour of conversation or heavy thinking. One work meeting or social interaction per day. By November, I was living a more normal life, able to go to an all-day work events, get public transport around the city without significant issue, and socialise fairly normally (though still avoiding late evenings or anything intense or noisy). I could also consistently walk 3km in one go, cook for myself, do house chores, and so on.

The December Collapse

In mid-December, I had a serious regression. The house of cards came tumbling down, the bubble burst. I don’t know why. My best guess is that, in the two weeks before, I had been doing a bit too much. While day-to-day I felt fine, deeper down, something had gone wrong. A jenga tower can lose quite a few pieces while still seeming stable. But it could also have been unrelated to what I was doing. I had noticed I might be overdoing it and had eased off for at least a week before. Normally, there would be smaller symptoms first, but day-to-day was good. Perhaps I picked up a new infection which did something. Perhaps the underlying cause, whatever it is, had been growing for some other reason.

On the Sunday before the crash began, I spent five hours playing the board game Diplomacy with friends. On the Monday, I seemed totally fine and did a normal workday (at home). On the Tuesday, 12th Dec, I walked 3km, feeling good, and then went to an event in the evening. On the walk to the bus, my heartrate had gone higher than usual, but I reckoned it wasn’t too risky to still go. At worst, I thought I would take it easy on Wednesday and bounce back to baseline by Thursday – as had happened many times. At the event, I was mostly lying down listening to the speaker – instead of sitting, which is physically more taxing — then chatted to people afterwards, lay down a bit, and left early.

On the Wednesday, I woke up with a mild crash, as I thought I might. I cancelled on going to an afternoon event I had planned and took it easy. On the Thursday, I felt pretty much fine again. I did some light work and and had a 45 minute phonecall with a friend in the evening. My biomarkers seemed fine in the evening. Yet on the Friday, I woke up with a medium crash. I went into rest mode, and started to feel alright after lunch. However, I had a late afternoon work phonecall scheduled which was fairly important, and decided to still do that. Again, I felt fine at the time.

On the Saturday, I woke up feeling bad again. This was worrying: I realised I might be in a worse state than I thought. I went into an aggressive rest, trying to do as little as possible. I spent the weekend lying around primarily watching youtube videos, moving around as little as possible, eating food that didn’t need cooking. I’ve had these sorts of rest days before. Mentally, if I notice I’ve crashed, I press a metaphorical big red button, cancel all my plans and work, eat low-prep foods, and take the day easy.

Yet after three days of this, the Monday a week before Christmas, nothing had changed. For three nights I had gone to bed expecting to feel better the next morning, and on three mornings I had woken up surprised to still be just as ill – fatigued, headache, weak, my limbs shaking as I went down the stairs. Usually a crash would only last about a day before bouncing back. Three days was bad news. As it happened, the whole ‘crash’ period lasted about two weeks, though there was less a clear ‘ending’ and more a blur into some sort of stability.

I had been planning to spend the Christmas days with my parents, my brother, and his wife. That was now off. I wasn’t well enough to pack or travel; making the journey by public transport or by car would risk making me even more ill. Even if I got there, if I couldn’t socialise anyway, what was the point. I didn’t mind missing Christmas that much – it’s become fairly normal for me this last year to have to cancel on holidays and trips. I also had to cancel a three-day holiday for a friend’s 30th around New Year’s Eve which I had been looking forward to. But my big concern was what this might mean for my health in January.

A friend came to stay with me for a couple of days. This had been planned anyway – she was back in the country over the holiday period, and around London for work happenings. I enlisted her to help me with things, sorting my food and bringing me things I needed. While I avoided any proper conversations, there was still talking while I explained things. We still exchanged words or a few sentences through the afternoon. I noticed that even her being in the same room prompted my brain to think of things to say.

The Depths of the Crash

The next day, I woke up even worse. The crash had gone to a deeper level.

Writing – too much. Few words only. V light sensitive. Thinking too much.

That would be how I would have expressed it, at the time.

It hurt inside my head and my whole body felt off. Probably not unlike a hangover, though I’ve never had one. Monitoring my biomarkers on my garmin watch, as I always did, I could see that my heartrate jumped up if I did as much as think.

I spent three days lying in the dark, wearing sunglasses indoors, listening to gentle music, and just breathing. Using my phone, watching a video, listening to anything, and even typing was too much for me. When I had to talk or write, I used and requested as few words as possible – “Water”, or pointing at things and making a grabbing gesture. If someone spoke to me, it would hurt inside my head, and I would often wince.

Thoughts would come to mind, my heart would start racing more, I would have more of a headache and negative feelings, and so I did my best to not think. I used empty mind meditation techniques. I watched the clouds, and imagined my thoughts as clouds which could float away. I imagined breathing my thoughts out with exhalation. I imagined my thoughts being water dripping into a lake to ripple and disappear. Then I narrativised this, my inner monologue describing how I was letting the thoughts go, which is itself a thought. Empty mind is difficult, but if I didn’t have experience of meditation from before, this whole crash would have been more difficult.

Any physical activity was tiring, as I was already exhausted. I shuffled and staggered around the flat, using my hands on walls to help me move around, unsteady on my feet.

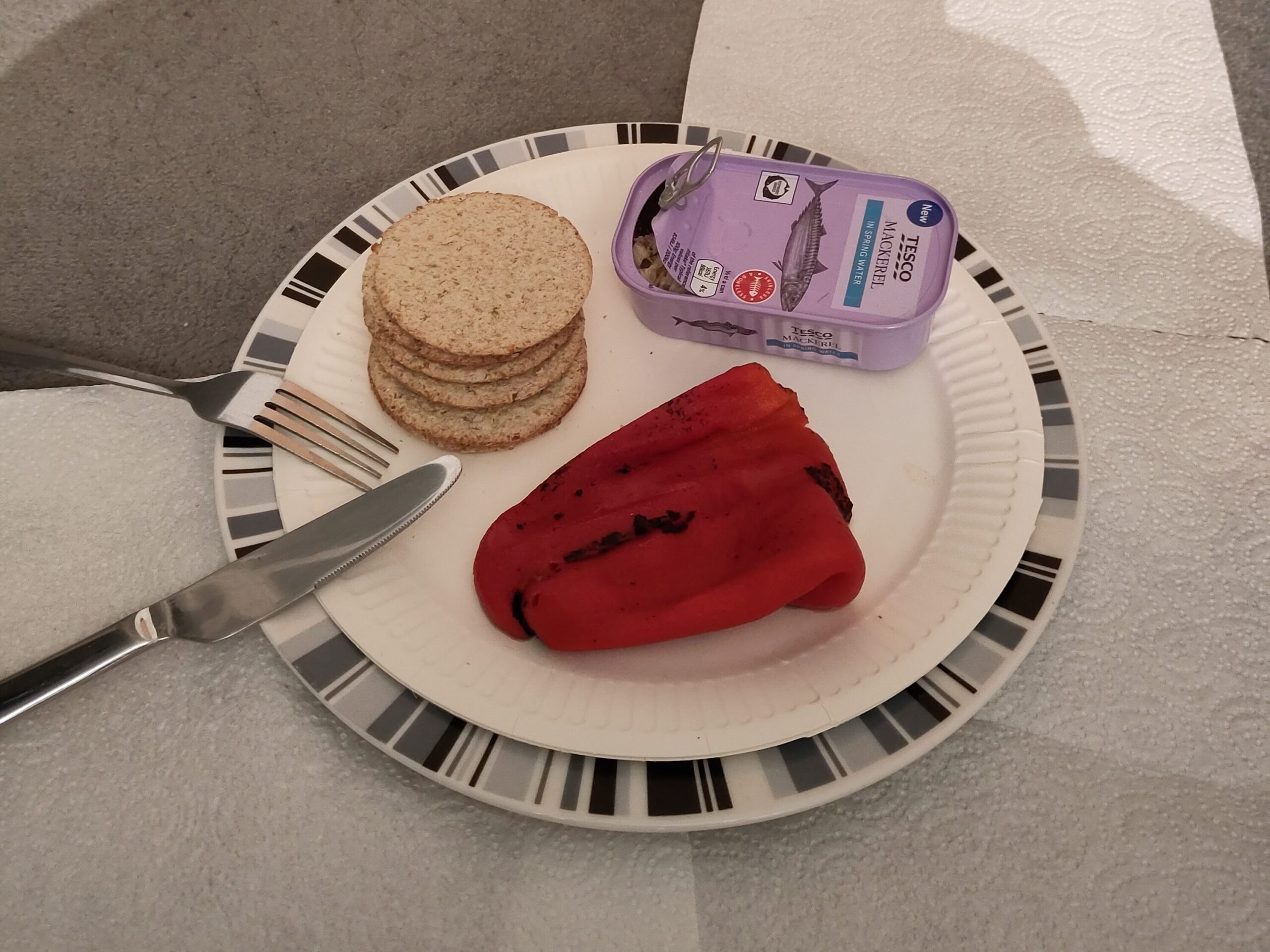

The absolute basics of living I broke down into small chunks, aiming for no more than 30 seconds at once (a standard protocol for this condition, to give the muscles recovery time and try to avoid anaerobic respiration). I prepared lunch one bit at a time: move tupperware from fridge to table; rest; move food from tupperware to plate; rest; microwave food; rest; remove oat cakes from packaging; rest. Eating, too, was spread out with rest breaks. Sometimes opening the plastic packet of a snack bar, my hands fumbling and trembling, was all I could achieve before taking another rest break. When going to the toilet, I would take a rest break after getting to the toilet, after using the toilet, and again after washing my hands.

I would lie in the hallways with everything within reach. Phone, water, clothing, food, spread around me, so that I could reach it lying down. Near the toilet, to reduce travel time. The basics of life strewn around me as I just lay there.

My nervous system was dysfunctional, and automatic breathing didn’t happen enough. This has been a problem the whole time — I realised when walking I had to manually breathe more, because my body wasn’t breathing enough for the exertion. It was acute. When eating, or brushing my teeth, I had to remember to breathe. Eating became a whole experience in which practicing mindfulness was essential. It turns out, eating was either stressful or a distraction enough that my brain would also start running away with thoughts, doubling the difficulty of this. So, while eating, I put on a meditation bell track that rang a bell every six seconds, designed for a breathing exercise, but I used it to help me remember to breathe.

My body also experienced significant heat intolerance – not a new issue, but now much more intense. If I lay on the sofa, the cushions I was on would heat up, and then my back would overheat. I noticed it in my heartrate going up, and could feel my back was warm. This was localised – my legs could be cold even as my back overheated. I lay on the carpeted floor, changing where I lay every so often as the overheating happened. Sleeping, I had to use a thin blanket instead of a duvet, because otherwise I would overheat at night, my unconscious body no longer able to manage it.

I lay there knowing that the symptoms I was feeling were because basic biological functions were not working properly. Exactly what still isn’t fully understood, but mitochondria in my cells were not working properly, both in my brain and muscles, and my body couldn’t regulate temperature. And knowing that there are currently no medical treatments or any guarantee of recovery. I was worried about the future (more on that to come later), though I think I did a fairly good job at focusing on the immediate recovery and keeping a positive mindset that I would have at least some level of recovery in a week or two. I knew that what I was now experiencing was the daily reality for some people, who become stuck in this deficit bedbound, barely able to communicate.

Dying was also on my mind. I think this is because we have an awareness of being unwell – people poisoned or terminally ill can often be aware – so my mind knew that some basic biological functions weren’t working. Though I wasn’t at risk of actually dying (and wasn’t worried about it), in terms of biological function I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that I was halfway to dead. And, if I got stuck severely unwell, would have half-died (though of course without the finality of death). This was similar to my bad couple of weeks last summer, though at that time my issues were around blood flow and temperature regulation instead of mitochondrial issues. Last summer I had written up an informal will/last wishes. This time round, I thought about my funeral. I mentally wrote myself an obituary (while also trying to stop myself thinking), and contemplated the idea of doing a half-funeral half-celebration of life at my next birthday, which would work whether I recovered well (to celebrate!) or didn’t (to grieve a half-death).

Help from Friends

I asked friends to come round and help me. Any activity that I didn’t have to do might reduce my energy deficit or increase my chance of recovery: if food could be brought to me on a plate, that was much better than having to prepare it myself. Some days in, feeling a bit better, I ordered a takeaway, even the effort of moving it from delivery containers to a plate, or the next day from fridge to plate, was too much. Let alone shopping, cooking, and the mental load of planning it all. So, I asked friends to help.

I messaged one friend who knew my needs fairly well and had experience in caring for ill people, and asked her to arrange everything, giving her a list of names and numbers. She messaged everyone, set up a rota, and wrote instructions. One of the pitfalls of being ill in this way is that arranging the care is too much, so as soon as I realised which way it was heading, I set up someone to be a coordinator/point of contact (and she also came round to provide in person care). .

This was tricky, and in some instances this caused almost as much harm as it helped, because of the need to communicate. It traded less physical exertion on my part for mental exertion. At the time, I thought it that avoiding physical was most important, but actually, it may have been the other way round. Or perhaps, in the unknown, striking the balance would be best. Even with the explanation and the general ask not to talk to me unless necessary, on some occasions the communication burden made me worse. Twice I regressed after someone was round to help because of all of the talking and thinking involved. It was also hard for me to not talk, it being so natural to do! People can’t read minds, and sometimes I would need to explain things. Most people couldn’t easily change their way of being and communicating to treat me like I was in a coma and just do things, and would ask normal questions. By the second week I made the instructions clearer, and a couple of visits worked excellently where I wasn’t spoken to at all.

It also meant I experienced both dependence and gratitude. While I’m familiar with being unwell in a few ways, I’d not been cared for in this sort of way for a couple of weeks before, nor in a way that was critical, where being brought food meant my chances of positive recovery were increased. There is something nice about being dependent on others for these basic needs (though only when it’s secure and positive for autonomy). I was surprised by how grateful I was for not much – someone delivering me a meal was very meaningful.

Receiving this sort of care is not the norm for most people my age in this current society, where individual independence is the norm. We don’t want to be a burden and trouble others, and most of us (at least men) don’t have these sorts of care relations, where friendships are more about doing fun things together. Almost commodified as fun casual relationships. I’m not meant to be sharing these sorts of socio-political reflections in this blog. My philosophical and political worldview has been about the importance of care for years, and how our society and daily lives should be structured around mutual support instead of independence. But this was my first experience receiving such care (though not of giving). It reminded me both how fundamentally normal this is for humans as a whole, where living in small communities with mutualistic care was a more common condition for humans than in modern individualistic social orders, and reminded me how far our current social structures are from this. (See also: the isolation that parents with babies often experience.). It was a bit awkward to ask, though I knew that these were all friends were, roles reversed, I would gladly provide such case. But I did feel the precarity. I think I only just had enough friends to ask for help to cover the gaps and without one person being overly burdened for more than a couple of days at a time, and knew that this would only be sustainable for a few weeks.

Out of the Deepest

After about three or four days of lying in the dark trying to not even think, I had a slight improvement. I still tired easily. Washing myself was just about manageable, the thirty seconds of arm movement to rub myself with soap and water, or drying myself with a towel, was still right on the limit. But I was no longer unsteady on my feet and feeling fatigued all over.

I was able to do some thinking without it being too much – without my heartrate jumping up immediately. Being free of the burden of trying not to think was a big relief, and being able to write small amounts on my phone was useful. I was able to watch some easy videos and listen to an audiobook without it being too much for my brain. Post-acute covid syndrome is a form of brain damage, and I was still quite limited. I watched the comedy TV show Taskmaster, which involves comedians doing silly tasks in competition and discussing it. No complicated information to process. I also watched videos of people going on walking adventures, which had nice views and stories of their obstacles. My favourite was Straight Line missions, in which someone had to walk from one place to another in a totally straight line, whatever terrain or obstacle in their way. I listened to the Lord of the Rings audiobook, because it’s a story I knew well. Any new audiobook would require more brain effort, with new scenes, characters and plots. This entertainment was much better than a hellish nothingness.

This was a huge relief. Instead of lying there in the dark, somewhat bored and trying to not think, I could now engage in light entertainment which provided some distraction for my brain. It’s a world of difference, and – as long as it stayed this way – meant I was out of the depths of the illness where basic mental activity and communication is too much.

Funnily, each of these linked into my daily experience. My friends (and on one day, my parents) had to figure out and complete tasks I set them with minimal instruction. I had lots of obstacles to overcome. Perhaps my climbing of the stairs – four steps at a time, with five minutes rest in between each step – was less difficult than Geowizard pushing his way through a dense pine forest. If Frodo could overcome the fear of the ringwraiths, perhaps I could move through my fear of this illness.

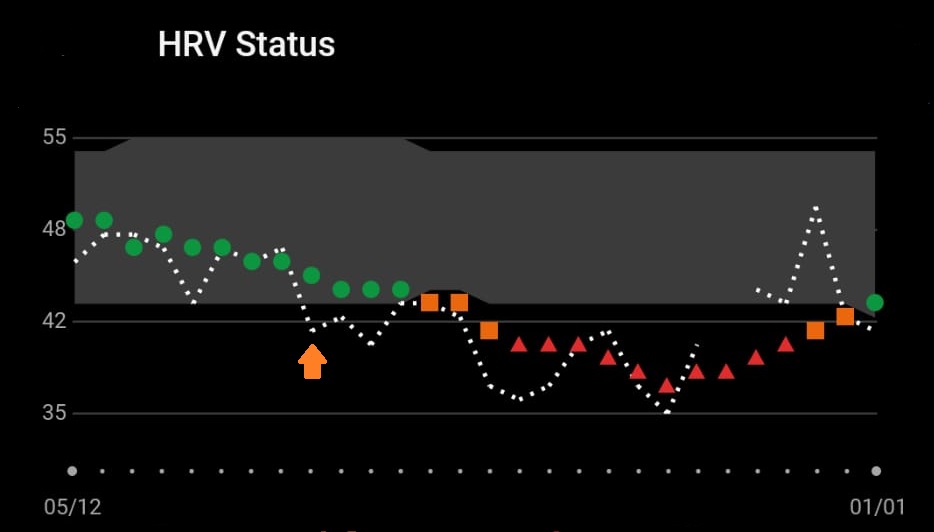

Yet even though I was out of the depths, it was not a smooth recovery. The HRV graph shown above tracks it pretty well, correlated closely with being unwell. After the crash deepened, on the 18th, I had started to climb out of the depths. Then, on the 23rd or 24th, I was knocked back down again. It’s a bit hazy, because I didn’t keep much of a day-to-day log, but I know that there wasn’t a smooth exit from the crash, and that there were something like three setbacks. I know that there was a day when I thought I would be more ok to do things but texted the friend on standby for emergency additional help. On the 30th, I felt much better. A friend came round to provide some food, and I was more on my feet, chatted a bit more, and used an electric beard trimmer to reduce my uncomfortable beard. The next day, boom, set back again. The invisible, unknown thresholds are very difficult to manage.

Medical Attention or Parental Care?

A couple of friends raised concerns about whether I needed medical attention. Which is understandable, given that I was asking for help with very basics, and that going to the toilet and washing myself were at my physical limit. Some also wondered whether I needed mental health support. Thankfully, these concerns were mostly messaged to the coordinator friend, who had a better understanding of the situation, but some of it still came through to me.

The reality is that there was no medical treatment that could help me. People with long covid sometimes seek emergency medical treatment, and rarely is there any benefit. In addition, the effort of talking to medical professionals, travelling, being in a hospital, etc, would all make me worse. What exactly is going on in post-acute covid syndrome, and in such a crash, is not known. Nor are there any treatments to help. When people go to the hospital with it, they are tested and monitored to rule out other possible issues. Often they are also told it’s just anxiety (for higher heartrate and stress, especially if they are female, or depression (for low energy). Yet many people have a belief that medical professionals can do something, and follow a norm of ‘if unwell, go to hospital’. This was a form of ‘iatrogenics’, of ‘healer-harm’, where somebody trying to help actually made things worse – both going to hospital to be treated and the effort of trying to explain to well-meaning friends trying to help that going to the hospital was a bad idea.

[Note: Now that I’m out of the crash and more stable, I am going through the medical system. But there are still no meaningful treatments available for the condition. Tests are done to rule out particular things, such as any heart issues. There are specific acute problems which can be treated, but which as far as I know I do not have. There are some low-level therapies that can benefit, such as breathwork and mindfulness, which I already do.]

The other suggestion was to go and live with my parents – still the current social norm, absent a Life Partner to care for you; significant care from friends not being so normal. Yet this meant a lot of mental effort in logistics and preparation, plus the physical cost of the journey. I was certain it was the right choice to stay in place for a couple of weeks, both to see if I could recover enough to life alone or to try to stabilise to a less fragile state before having to do the journey.

What next?

The big questions on my mind throughout were about what would come next. Christmas being cancelled wasn’t the problem; where my health would be in January was. This was carrying a lot of stress and taking up a lot of mental energy to both think about and try not to think about.

As mentioned already, might I be stuck bed-bound or in an awake coma-like state, unable to recover out of the deficit? If I recover from that, where to? How long before I return to a more normal state of daily living, as I had reached in November – or perhaps I might never get there, given that the December relapse showed that I was still very fragile with this condition even when I felt like I had recovered a lot?

Would I have to leave London and live with my parents? The current level of care needs probably couldn’t be sustainably met by friends, and one thing that had made it much easier in the Christmas break was that my flatmate was away. I couldn’t do domestic chores or keep things very tidy, so that would be a problem. Would this be for a short time, or end up being for the medium or long term?

Perhaps most prominent in my mind, because of the imminence of deciding, was that I had been offered a teaching role at Birkbeck, where I was doing my PhD. One evening per week, teaching environmental law. Through a fluke, I had been offered a grade higher than the usual entry grade, presumably because nobody had applied for that job – Birkbeck doesn’t really do environmental law, with only one existing lecturer doing it and no other PhD candidates. That would be a shame to lose both the opportunity and the income that came with it, which would make up my monthly financial needs.

Would I be able to continue my current flexible part-time job at Lawyers for Nature, or might I lose that? Would I have to take time off my PhD studies, just when it seemed like I was getting to a good place in it? This one, at least, was the most flexible and had the least lost as a result.

Finally, what would this mean for my non-work life. I had already stopped almost all of the exercise I did, save for local walks, coaching parkour and sometimes going to a ballroom dance class, though I had been hoping I might be able to begin some in the coming months. What about time with friends? It was only in the last couple of months I had been able to (sometimes) go out of the house to meet friends (pub, cafe, party) and have normal conversations. Would I go back to social isolation again?

There was a lot to lose, a lot at stake due to this illness. These worries went round and round in my mind – to be clear, I’m pretty sure this was in a psychologically normal way, anxious thoughts around significant life being the normal response to such a situation, instead of a mental disorder – and I also found myself doing imaginary bargains with an imagined higher power. This served as something of an exercise in acceptance. In a Deal or No Deal type bargain, were I offered this level of health for January, would I accept that? Mostly, I settled on the idea that I would be okay if I wasn’t stuck with severe chronic fatigue, lying in the dark unable to do anything. If I could handle some mental activity, communicate in a limited way with friends, and do a couple of hours of work per day, then I reckoned that would be enough. In the depths of illness, that was what I hoped for, accepting everything else I stood to lose as lost. But, for these bigger reflections on grief and acceptance, I think they merit a separate blog post…

Postscript

This writing represents my thoughts during the second half of December and perhaps the first few days of January. As is often the way with my writing, it was formed in my mind, and then I had to do the work of putting the thoughts into a format others can read, as opposed to a writing process where the ideas unfold and develop in being written. What happened next in the story is that in early January I went to stay with my parents for, I hoped, a couple of months, and my health has improved, slowly and gradually in a bumpy way that meant it isn’t clear if it is improving much at all. The actual writing was done in small chunks through January and February.