Around the beginning of December, I started to reflect back on the year. I typically write about it privately, in a blog sort of style. But this time round, I felt I should write it publicly. It also took a bit longer than I had hoped, but, here we are.

Structure

You might want to skip some of this, it’s quite long. The 2023 Parts 1 & 2 are about what happened that year. 2023 Part 3 is about becoming severely ill. Parts 4 and 5 are my reflections on grief, loss, letting go, acceptance. Part 6 is the summary.

For the abridged version, you can just read Introduction/Overview, 2023 Part 3, and 6. Ultimately.

- Introduction/Overview — a summary of the whole piece

- Background: Pre-2023 and my Main Work on legal theory

- 2023 Part 1: Spring and Growth: First half of 2023, and achievement.

- 2023 Part 2: Summer, Illness, Loss: Becoming very ill, then somewhat recovering.

- 2023 Part 3: It was coming together, then it fell apart.

- 4. Reckoning with an Uncertain Future

- 5. Grief and Letting Go

- 6. Ultimately: a summary/conclusion)

Total reading time: estimated 35-45 minutes.

Introduction/Overview

In early December, the themes and feelings of yearning, achievement, fragility, gratitude, acceptance and resilience were all in my mind. I felt I was getting into a good place in my life, and though I had been severely and moderately ill with post-acute covid syndrome, things were trending in a good direction. In the middle of the year, for about a month, I got to pretty much exactly where I had been trying to get to in life. I almost couldn’t believe it – especially given that two months before it seemed like it was about to come to ruin. Then, in the summer, my health got much worse and two of the four pillars of my life collapsed. Gradually, gently, I improved. Come November, I was in a fairly good state health wise, and in early December, it looked like come January, I might have rebuilt things again. Yet, suddenly, a severe health decline, and this time, three of the four pillars collapsed. I spent a couple of weeks feeling about halfway to dead. That is sort-of metaphorical, because I wasn’t actually at risk of acute death, but it’s also a true description: my body had some fundamental dysfunctions; I had lost over half of my capacity and capability; and may never recover to have more than half. In the depths of this, though, I came to a core essence of trying to accept it for what is.

The core message is something like: being alive is better than being dead; make the most of it. And that there is little point dwelling on what I don’t have, and focusing on the positives of what I do. Some version of this sort of acceptance seems to present in buddhism, stoicism, and christian thinking (though it’s different in each of these and there is more to each of these than just this!). This blog is the long version of the story.

Most of these thoughts happened in December, and I wrote some of it slowly in February and March, then finished it off in bits and pieces through to the end of July. I’m out of the worst of it, and much better than I was in December, but still very ill. Recovery happens gradually, and relapses are always possible. It is far from guaranteed that I will recover to a good state of health. My hope is that in five years or so there will be medical advances such that treatments and cures exist.

This blog post combines two things: what happened in my 2023; and my thoughts on loss, acceptance, etc. The themes are mixed into what happened, of course. If it reads something like an obituary, that’s because it half is. In the loss and grief, I was mourning what had been post. And it makes sense, given that I half-died.

Background: The lead-up to 2023 and where I was at the start of the year

My Mission

Years ago, after finishing my studies, I developed a mission in life. I was acutely aware of the dire political state of things – I think I was a few years ahead of the mainstream for seeing what was happening with social and ecological breakdown. I knew that my aim in life was to contribute to working towards a better society. I studied law, and it became apparent that the overlap of law, philosophy and politics was where I should be working. This area had the magic combination of there being a huge gap there with hardly anyone working in this area, but it was important work that I was good at.

So, I knew that working on developing ideas for how our legal system needed to change towards a just and harmonious society was what I should be working on – and I termed this ‘Interconnected Law’, so that I could give my project a name. Through my studies and thinking about legal theory, it became apparent to me that both how we thought about law and the legal system itself needed to change if we were to move, as a society, in a good direction. Law is generally seen as a neutral, technical system, but it is not. It produces and reproduces various cultural norms and social relations, and the conceptual foundations and practical operations of the legal system are hugely important beyond the more immediate ‘what the law is’ which is the primary focus of political and policy discussions. Thinking about law in this relational way, and in a way that encompasses both social and ecological relations intertwined, is vital if we are to work towards a just and harmonious society. There’s the summary of my work (and you can read more here, etc, if you are interested.)

This isn’t the only thing I think matters in my life, or the only thing I do. I also find meaning in work that cares for or empowers people, which I found in coaching parkour, and in relationships, and in doing political work, and the meaningfulness of simply existing and experiencing the world. But this is the primary mission, so to speak.

Early “Career”

Through a series of lucky breaks, I got work experience as a legal researcher, working for an MP, doing some writing, and as operations manager for a tiny campaigning NGO. I had been intentionally seeking out experiences which would both help me to understand how to work on social change and get the relevant life (and CV) experience to work on it.

These jobs were paired with coaching parkour. I started practising when I was 17, and at university ended up establishing a parkour community, which I informally coached. When I moved to London for my masters, I got the proper coaching qualification, and after my masters started teaching at the Foucan Academy. This helped out financially, for sure: while the MP job was salaried at 0.8 FTE, the other jobs were part-time, and it was only combined with coaching parkour that month to month I had just about enough money coming in. But it was also a passion. I enjoy being physically active, and I also enjoyed teaching, having thought seriously about becoming a schoolteacher when I was at uni. Coaching was fun and rewarding, and what I taught was just as much about personal development as it was about the movement practice (especially for young people). Through parkour, people can be taught to better work through their emotions, overcome mental hardships, become more confidence and autonomous, and become better people. I taught teenagers to take responsibility for themselves, and wove in life skills about communication, helping others, being more comfortable with having emotions (it was mostly teenage boys), the importance of fitness, and having more confidence in oneself. Doing coaching work also helped to balance out the theoretical political work, being involved in helping people immediately with something practical.

Moving Forward with Interconnected Law

After graduating, I knew there were a few pathways for taking forward the legal theory work. I could chip away doing small bits of writing and projects on the side of however I was earning money. I could get a job in a suitable NGO/think tank. Or I could try and do a PhD.

I did the first for a few years, and I was able to develop my ideas, write a few articles for online platforms, and give a couple of presentations which I was proud of. As for the second – while I tried to reach out to a couple of organisations, there didn’t seem to be any working on the sort of legal change I was thinking about, and the idea of Rights of Nature had not even made it to the fringes of the mainstream. Nor did I have the confidence to do a good job of networking. I did the other jobs to build up relevant skills and experience to support the legal theory work – how to conduct research, how to run a small team, how to write publicly, etc.

In 2022, I finally took the leap to start a PhD, as being the only other option. It took me a few years to be ready as well, and develop enough confidence in myself to give it a go. I enjoyed academic work (sort-of), and having already tried the other two pathways, it seemed like I should give this one ago. It would allow me time to really work on the legal theory, and mean I got taken more seriously too.

Unfortunately, though, I wasn’t successful in getting funding: it’s “very competitive”, meaning that there is hardly any funding available. Funding has been reduced through the last decade, and government policy is about ‘economic growth’ and research with immediate impact. While I knew that my work was pioneering, this also meant it would be hard to get funding. for.Academic funding – and charity grants – generally follow a model of ‘I am going to apply X to Y problem and Z will be the outcome’. The application has to be very tight, usually needing feedback from multiple people who know the system and somebody on the inside to argue your case. A PhD student isn’t meant to come along and say, ‘I am going to do novel theoretical work to fill this gap’, and I got feedback that my proposal was too “ambitious”. I also faced a difficulty that my proposal was trying to solve a problem that most people didn’t even recognise as existing. Of course, I had weaknesses too. Maybe I wasn’t good enough. My undergraduate and master’s results were good, but not amazing, and this will definitely have held me back in grading. Nonetheless, I think it was a combination of the two.

So, I didn’t get funding before starting. But, my parents provided me with one year of funds so that I could have a go at chasing my dream. The main expense is cost of living, the PhD tuition fee is only a fraction of rent and food costs. The idea was that this would allow me to try it out and see whether it was something I wanted to stick at. There were then two options: be successful in getting funding after applying again (it was possible to apply again in the first year); or figure out a way to continue studying part-time (by working around the PhD to get enough to live off).

So… with all of that background over, now I can tell the story of 2023.

2023 Part 1

Legal Theory Work and Confidence

The year started with two big deadlines. One was my PhD funding application; the other was a writing competition I was entering. I started the PhD the previous autumn, so at the start of my second term I was again going through the funding application process. I approached it with some nerves; there was something about it that was always quite difficult for me to engage with, around the fear of failing and importance of the work. This was my second year applying. I was given feedback from my supervisors, the head of the PhD programme, and three other PhD students. I revised and polished my application, attempting to tailor it to be a better proposal with a tighter focus and more achievable outcome.

At the same time, I worked on an entry for a writing competition, the Nine Dots Prize, “a prize for creative thinking that tackles contemporary societal issues”. I came across it in the autumn, when they announced that the question was “Why has the rule of law become so fragile?”. A question at the intersection of law and politics, and after mulling it over for a couple of weeks, I realised that this topic was basically an ideal question for me. My undergraduate coursework (which won me the prize for jurisprudence, which was the whole spark for me having the notion and confidence that I should work on legal theory) was on the Rule of Law, and I reckoned I had a good angle at this question. Of course, I didn’t win it. But in working on it, I developed the confidence that my ideas were good, and that I could write something good, and I came to imagine myself as someone able to win the prize.

Similarly, after working on the PhD application, I was proud of it. As it happened, I was not successful in getting funding this time round either. Yet despite this, I developed the confidence that I was someone who knew what they were talking about and could write a good PhD project. My supervisors were both great, believing in me and my work, and having someone else see the potential in my work and offer some support helped a lot.

There was also a Rights of Nature event organised in February which I was invited to, which brought together various people working on the topic to hear from a visiting expert and discuss our thoughts. This was my first time meeting most of them, and wanting to be treated as an ‘equal’ who had something to contribute. I went in quite nervous, but think I did a good job in sharing my thoughts on the topic.

So, the first few months of 2023 saw me reach a really good place in actually having confidence in my work and ability. For the years up until this, I had this strange headspace where I both knew that my ideas and ability were good but felt such doubts and dread about it. This was a huge development. However…

Health and Exercise

Alongside all of this, I was still recovering from getting infected with Covid-19 in April 2022. Thinking back on that health period is strange… but after a few months I was able to live a fairly normal day-to-day life. Looking back at my calendar, I was able to travel on the train and meet up with people, but my ability to exercise was quite limited. I had been trying to find the balance of not doing too much, while still wanting to do the exercise that I could to keep fit. On many days I was fine, but often tired, and I would often experience what we call “crashes”, where after doing too much I would feel a lot worse the next day – you wake up feeling exhausted, with a headache and blocked nose. I often had days where I could only do a couple of hours of work and had to rest.

If I knew what I knew now, I would have done things differently. But I was trying to find the right balance of doing without overdoing, and being careful. And it was working – month by month I was getting a bit better.

I went to two martial arts groups, and tried to find the balance where I could train without overdoing it. I did the light exercises but didn’t push myself physically to do the harder stuff. Probably about half the time it was fine, and the other half I overexerted myself and had to suffer the consequences the next day. One of the groups was a great group of other leftie people and a good collective vibe, and I was enjoying gradually becoming part of that group.

I also continued to coach parkour, doing my best to coach without doing much physically. I avoided doing much demonstrations, and the assistants I worked with were understanding and happy to do all of the equipment moving so that I didn’t have to carry heavy things. This made it manageable for me, to just be on my feet, walking round, leading the session and talking to the students without doing as much physically – but this was still exhausting, and I would often have crashes the next day.

April/May dilemma

Around the time of April and May, I was facing a big problem. I found out that I had not got been successful in getting the PhD funding. I had allowed myself to dream that perhaps I might win the Nine Dots Prize (which would have been enough money for me to the PhD for a couple of years), believing that the work I had done was good enough to win – though also recognising that, just like in many job applications, there will be many entries which are good enough in different ways, and it comes down to the judges’ preference… but of course, I did not win.

So, I faced the problem that I did not have a financial way to continue the PhD… The only remaining option was to go part-time with the PhD and get enough money from part-time work to live off. Coaching parkour (evenings and Saturday) gave me perhaps half of what I needed. If I could find another job for 2-days per week, technically it would be possible. But the reality was that (1) finding the magical job which was for just 2 days a week would be difficult, and (2) that my health was not up to having a job, given that once or twice a week I would crash and have to spend the day resting anyway. I had a chronic health condition that was not compatible with doing a regular hours job.

Things were looking bleak. I was worried about what this meant for the future; it seemed like my only real option was going to be to drop out of the PhD and somehow find a job. I never got to crunch time, because my decision was to focus on the PhD for the first year, and postpone dealing with this problem until the summer.

May-June: Three Big Changes

As it happened, things turned out differently – in a way that gave a good example of why worrying too much ahead of time is often pointless. With such things I always think back to a passage from the Bible:

“Go to now, ye that say, To day or to morrow we will go into such a city, and continue there a year, and buy and sell, and get gain. Whereas ye know not what shall be on the morrow. For what is your life? It is even a vapour, that appeareth for a little time, and then vanisheth away.For that ye ought to say, If the Lord will, we shall live, and do this, or that.” (James 4: 13-15, King James Version)

Or, in the New International Version:

“Why, you do not even know what will happen tomorrow.”

At the start of April, I got an email from the organisation Lawyers for Nature (LFN) saying that they were looking to hire a research assistant for 2 days per week. This was almost unbelievable… this was the ideal 2/days per week job that I was looking for, for an organisation I wanted to work for! It was established by 2 people (Paul Powlesland and Brontie Ansell) who were doing work on Rights of Nature, and was essentially just a brand for the two of them to work under. I had met Paul a few times over the years at various events, and met Brontie for the first time at an event in February (the one I mentioned earlier).

Remember earlier when I said that one of the pathways for me to do my mission-work was to work for an NGO doing that work, but that none existed? Turns out that LFN they had got some funding for a research project and were looking to hire someone. It seemed to good to be true. So, I applied for the job, seeking to demonstrate that I was knowledgeable about rights of nature, had experience as a research assistant and working in a small team and so on. This was genuinely the job I had been getting ready for for the last five years. I was invited to interview at the end of May, and in early June was contacted to be offered the job. Dream come true. (The good news: with the health decline in December 2023, after two months of leave, I returned to this job one day per week in March 2023. It’s the one thing that I was doing that I have been able to continue.)

However… one step forward, two steps back. In May, my health also got much worse. It didn’t happen suddenly, but throughout the month. After months of getting gradually better, the direction changed. I did too much, going on a weekend trip to the lake district (with other environmental law people). The train journey with my big rucksack was actually too much, and caused an issue. On the Saturday, I went on the five hour hike. I felt ok enough during it, though noticed that my heartrate had got higher – a sign that it had been too much for me. That evening, I joined in with the dinner discussion and after-dinner socialising. This is one of the funny things with long covid: it can feel ok at the time, but not be ok. The next day, I woke up exhausted, and didn’t join in with the hike on the second day. I had a restful morning, and by the afternoon felt up to a short walk by the hostel, and again joined in with the evening discussions.

Three days after getting back home, I thought I was back to normal. And had a week that seemed normal. But then I overdid it at a martial arts class, and then declined for a couple of weeks. A significant day was my Grandad’s funeral in the middle of May. I woke up having already crashed from the previous day, but decided to push through, get up, get on the train, attend the memorial service and the funeral ceremony, which included giving a eulogy. Overdoing it on a day I was already unwell is dangerous, but at the time I didn’t realise quite what I was risking. It’s a really strange condition, with the unknown thresholds and lag effect of overdoing things. I tried to strike the balance in taking it easier by still doing things, but come early June, I had got worse and worse. I realised that actually, things had got quite bad.

There were two big moments when I realised things were quite bad, and that I wasn’t bouncing back from these couple of weeks. The first was on my way to coach parkour one evening. I walked over the bridge to the tube station, and when I got to the tube platform, my heart was racing. It stayed racing on the tube and sat at the cafe the other end. Given that my body was unhappy from this walk and wasn’t recovering just sitting in a cafe, I decided coaching was a bad idea, and called off sick. I never returned to coach at the Academy. A few months later, I told them I reckoned I was well enough to return to coaching under the same arrangement as before, or be an assistant coach. Sadly, they said that they only wanted me if I was back to full health. The message didn’t even come from the Director, and nor have I heard from him since to ask how I am or wish me well. It’s a sad reminder that even when you went above and beyond to give a lot in a job – not only to the students, who it’s really about, but also helping him out (for free) with logistics and troubleshooting here and there – to many people, everyone is disposable. Whether returning to coach would actually have been wise – probably not, so it was probably for the best, though they could have been… nice… about it.

The second was a friend’s wedding I had hoped to go to, in my hometown. I realised that I wasn’t well enough to make the journey the day before, and nor was I even well enough to go along only to part of the wedding (I knew I wouldn’t be attending the whole thing like a normal guest). Cancelling going to the wedding was when it really hit me… I was really ill. It was one of the few times that I cried from the weight of it all – not that there’s anything wrong with crying or being sad, but otherwise I had mostly just been going with the flow.

2023 Part 2: Summer

I hit the brakes and reduced life down to what would hopefully be manageable and recoverable. I had a few rough weeks, a difficult couple of months. The hot weather was difficult, with my ANS not well able to thermoregulate. Thankfully, month by month, I gradually recovered. By October I was starting to feel stable and on the journey of recovery. I still tried to strike a balance and occasionally have friends visit for a short time, and went on to a couple of work-related events. It’s strange to think back on, especially from where I am now. I was severely ill but still managed to do a few things during that time, either because it was worth the risk (a few important work events) or because I wanted to have some social time, though I didn’t know how much social activity was safe for me. I took the hit afterwards, but thankfully I still was on a recovery trajectory. I don’t know whether I would make different choices knowing what I know now.

Adult Parkour Classes

One of the joys of 2023, from mid-April through to October, was the adult parkour sessions I ran. At the start of the year, one of the top-line aims of the year was to be running my own adult parkour sessions. I had given this a go in 2022, with partial success; that year had two regulars, a friend and an acquaintance who were both interested, and a handful of people who came once or twice. This year I wanted it to establish properly, and I achieved this! I received a few emails as people either found me online, saw a flyer I put up, or heard via word of mouth. After the initial weeks of just 1 person, then 2, by late summer it had grown to 4 solid regulars and 3 bonus people who came a few times.

This was a joy, usually a highlight of my week – especially given the illness. It was a great group of people, and everyone was understanding of my limitations. Two people who came hadn’t done any other exercise as adults, and I got to lead everyone through my flavour of parkour.

It was difficult, of course, with my illness. I did my best to do nothing more than minor physical demonstrations, but it was still focused and on my feet for some time. Often I would crash the next day. I was also using it to test my physical limitations – it was the most I did each week, trying to find what was safe. Especially as I was no longer coaching at the Academy, this was a great reminder that I was good at something. I enjoyed the feeling of planning a session, intending some particular threads to come through, then leading the group through it and having things come together.

Unsurprisingly, the group dwindled through autumn, and when it was down to 2, we wrapped up for winter, hoping to start again come Spring.

Social (Half-)Death

Losing my ability to exercise has been difficult. Losing most of my ability to work has been difficult, though at least I can do an hour or two a day at the moment, it’s scary to imagine that I may lose that too – and lose connections, currency, etc. Losing my ability to live independently, physically and financially, has been difficult. Another dimension that has been very difficult – without wanting to compare or rank these different things – has been the social loss.

Just like I at times feel like I have half-died physically, it feels like socially, I have half died. The illness also impacts relationships. Social time only happened when people came to me. That already reduces the possibility by more than half, and meant I couldn’t join group things that happened. Later in autumn, I became just about able to travel to meet people, but even then, only if it was a good day, only if it was a journey and plan that worked for me. For a few months, I could only do about one hour of talking per day. So if I had a work meeting, I couldn’t also socialise.

In July I organised a belated birthday celebration with a handful of people. All of them knew I was il, and had spent some sort of limited social time with me in the summer. I planned it to be in the park by my flat, asked a couple of people to help me carry things. Though I said in the organising message that “I can’t handle all that much socialising at the moment so I’m after more relaxing company, quieter and slower pace conversations instead of the usual high intensity of socialising”, this… didn’t happen. I wasn’t a loud party, but it was three hours of typical amounts of conversation. After an hour or so, I hit my limit, but was trapped. My mindbody was freaking out, in fight or flight mode, having crossed whatever mysterious underlying problem was going wrong in my body. I may have outwardly appeared fine, some mixture of fight/freeze/fawn response keeping me talking to people, but I was not fine. I had hoped that me saying to people that I needed quieter and slower conversations would bring this about, but it didn’t; clearly it needed a more explicit facilitation. This ended up being quite upsetting, and really drove home how difficult socialising would be. The next day was a hard crash, all the more upsetting because of what it represented.

There’s also a question of what relationships and friendships are about. Lots of them, especially male ones, and the more casual acquaintances, it is about doing things together. I no longer had the friends I went bouldering with, and I couldn’t go to the martial arts training and join them at the pub afterwards. I couldn’t go to events I used to go to. I couldn’t go for a walk, join people to play board games, or go to parties, or go for a walk. When I did spend time with someone, I was often limited in terms of conversation, unable to have normal conversations. Relationships became limited and imbalanced. Ultimately relationships are meant to be two sided, with both people benefitting. Having someone spend time with me became more like an act of care or charity someone was doing for me, and I don’t think that’s just a feeling.

It also became much harder to make new friends, or work ‘networking’ type things. I couldn’t be out doing things that would lead to meeting people, and when I could, the follow-up was more limited. Let alone a new romantic partner. I’m acutely aware that I now have much less to offer in relationships – friendships, with family, or the romantic kind. Most people don’t just want a pen pal. I can’t bring as much to them, whether in doing things together or time together or care or anything else. With romantic relationships, not only are there the barriers of arranging things within limitations, but why would somebody choose to get into a relationship with someone who can’t do most things, can’t travel, and has to spend lots of time resting?

(Now, writing this in 2024, I am even more limited, not able to leave the house and only able to handle a few minutes of conversation at at ime. So, it got worse…)

This wasn’t a shock – I knew it was coming. Friendships either happen organically, through something shared together, or they require effort. When someone drifts away from a relationship, if the other person doesn’t try to reach them, then the people can drift apart. I have much less ability to put into relationships now; pen pals is about all I can offer. And as I said above, what a relationship with an ill person entails is different to what it was when they were well.

I don’t mean to blame people for that, nor to be pessimistic; this is just the brutal reality of having such a limiting condition. Socially, it is a half-death.

I’m glad, at least, we have the internet, and digital technologies for social and parasocial relationships. Being able to communicate through the internet and by typing on my phone is worlds apart from what this illness would have been like even 20 years ago. Having my illness in the current moment – technologically and socially, that I live in a stable place with my material needs met – is so much better than having this illness without digital technology or care needs being met would be.

Autumn

My health improved, month by month. I became more able to do work, go on short walks, and so on. In October and November, my capabilities increased. In mid-October, I was able to get public transport to events for an hour or two and participate fairly normally. In November, I got back to 80-90% of normal daily activity ability (ie not exercising). I could go to discussion events, I was able to meet friends in a pub or cafe for an hour or two, and I could walk 2-3km. I still had to be careful, and things didn’t always go smoothly. I would crash if I had overdone it, and it wasn’t totally clear what was safe to do. I had to cancel a fair few things still, and there was one party at a pub I went to where my bodymind freaked out at the noise and stimulation. But in general, things were on the up.

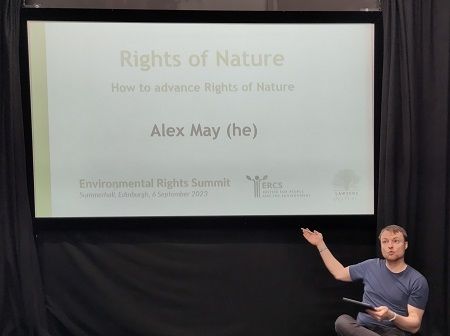

Work things were also going well. I had settled into the LFN job nicely. I gave a talk on Rights of Nature at an event, and I published a research report I had been working on. My PhD was coming along, reading and writing various of the strands I was going to weave together, and I was gearing up to write the 10,000 words I needed to submit for spring. I was feeling confident in myself and what I was doing.

2023 Part 3: Coming to the End of the Year

It was about to come together…

In early December, I started to reflect on where I was in life and how the year had gone, as I often do. I was thinking about what I had managed, and what I had lost, and it started to form into this blog post. I was sad about what I had lost due to illness, and my uncertain future, but I was happy with what I had achieved.

The big uncertainty was money. The LFN job 2 days per week was not enough to live off, unsurprisingly. Coupled with coaching parkour, it worked out, but I couldn’t do that. So, from January, somehow, I needed to start earning more money, and I also needed to make good progress on PhD work. I had a couple of ideas but nothing easy presented itself.

Then, suddenly, an opportunity dropped into my lap. My university advertised for teaching roles for the next term. I applied for a tutor role, did an interview, and got offered a job. Incredibly, I was offered a job teaching environmental law at the grade higher than the tutor one I had applied for – it had the job title ‘associate lecturer’ and the job description said you had to have teaching experience, so I hadn’t applied for it, but apparently they didn’t have anyone as they offered it to me. The timing wasn’t quite right, as I would have to learn lots of environmental law and prepare the module (instead of teaching existing content), while also working on my own research, but it would hopefully just about be doable. It was one evening per week, plus all of the prep time – hopefully not more than a day – and would pay enough that I would just about break even.

Wow. Had it really just come together?

… then, it all fell apart

Quite suddenly, my health deteriorated over the course of about a week. I don’t really understand it. It’s a strange health condition. On the Sunday, I spent the day with friends playing a board game, all seemed fine at the time and the day after. On the Tuesday, I walked 3km, felt great, and went to an event in the evening. On the way to the event I felt a bit off, but nothing too bad. On the Wednesday I had crashed, cancelled my plans for the day and rested. On the Thursday, I seemed back to usual, and had a couple of meetings, but everything seemed fine. Then, I crashed again, and again.

I don’t know why. Perhaps I had done too much over the previous few weeks, that something deeper down had gone wrong even though day-to-day I was feeling fine. The foundations had been eroded, or something. Perhaps something else had gone wrong – in mid-November I had started to develop painful swelling in my fingers, so, perhaps whatever caused that also set off the collapse. Who knows.

I’ve written about my experience of the December crash in this blog post, so I won’t repeat much. For about ten days, I was really unwell. My brain couldn’t tolerate anything – no screens, no talking, no listening, not even light. I lay in the dark listening to calming music. I could barely walk. I arranged friends to deliver me food, which I would eat lying on the floor. I tried to do as little as possible and hoped I would recover.

4: Reckoning with an Uncertain Future

Thinking about the future

The big questions on my mind throughout were about what would come next. Christmas was cancelled, but that was fine. My worry was what might happen next.

People with post-covid syndrome, or chronic fatigue syndrome in general, can become so ill that they are essentially living in an awake coma. Bedbound, unable to talk or do anything. If your energy threshold becomes so low that daily survival is too much, you might get stuck there. During that time, I worried that this might be me. I really did not want to get stuck at that level of suffering.

If I did recover out of it, how long before I return to a more normal state of daily living, as I had reached in November? Or perhaps I might never get there, given that the December relapse showed that I was still very fragile with this condition even when I felt like I had recovered a lot?

I might have to choose between the LFN job and the PhD work and the teaching job. Maybe I couldn’t do all three, but maybe I could do two. Or what if I could only do one – which would it be?

Would I have to leave London and live with my parents? Either for a couple of months, or if I couldn’t afford to live on my own due to losing these jobs?

And, what would this mean for my non-work life. I had already stopped almost all of the exercise I did, save for local walks, coaching parkour and sometimes going to a ballroom dance class, though I had been hoping I might be able to begin some in the coming months. What about time with friends? It was only in the last couple of months I had been able to (sometimes) go out of the house to meet friends (pub, cafe, party) and have normal conversations. Would I go back to social isolation again?

There was a lot to lose, a lot at stake due to this illness. These worries went round and round in my mind. I’m pretty sure this was psychologically normal thoughts responding to what going on, not a mental disorder.

Acceptance in the Darkness

I also found myself doing imaginary bargains with an imagined higher power, mental negotiation as I sought acceptance. In the depths of it, I was imagining what type of life would be bearable and worth living. Severe incapacitated post-viral syndrome, unable to leave bed, unable to talk to people… is a living hell. I was there for a week or two, and it was rough. The feeling of being in an energy deficit, the inflammation, the nervous system being imbalance… resting with this condition is not the pleasant sort of rest that one might find lying on a beach or lounging in a park!

Two things came to my mind. The first was the sentence “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”, which came in my mind as I struggled through my own sisyphean task of lying on the floor in the kitchen or hallway for hours, doing the bare necessities of eating and using a toilet in small amounts at a time. The second was Victor Frankl’s book, Man’s Search for Meaning.

“One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” is a reference to a Greek myth of a man who pissed off the gods and was cursed that everyday he must roll a boulder to the top of a hill. It would of course fall back down, and the next day he must do it again. The idea is that in the suffering – a painful physical task, and one which is pointless – the only option that remains is to find meaning in it. The line isn’t to say that Sisyphus was happy, I don’t think, but to say that this is how we must imagine being in suffering. A couple of weeks later I looked it up and found that it’s from Albert Camus, an absurdist/existentialist philosopher, from his book The Myth of Sisyphus.

It’s an area of philosophy I’ve only casually engaged with, but from my experience of thinking about such things, it seems that my position is fairly similar to what Camus said. Life is absurd, at many levels. Should I be sad about losing certain hopes and dreams? I don’t know Camus’ exact answer, but it seemed to me that the point is to find meaning in the struggle. Interestingly, I found that the book starts by saying that the most important question in philosophy is, why not suicide, if life is [objectively] meaningless and absurd. The question isn’t about ending one’s life, but about why we should live in the first place, instead of simply not existing? And it turns out that the line before the one I remembered was “The struggle itself to the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Man’s Search for Meaning is about the author’s experience as a psychologist who was taken by Nazis to a concentration camp. I read it years ago, and the thing I took away from it was this idea that having a purpose, a strong why, helps us through difficult times. Frankl thought that those who had – or kept hold of – a strong purposive drive were better able to endure the horrific conditions of the concentration camp.

These thoughts were in my mind as I faced up to the possibility of the future, and how ill I might remain. Would I be strong enough to endure this level of suffering? I at least hoped that in five years, there might be enough medical developments to understand the cause and have some possible treatments for the condition, so I might only have to endure five years of bad health before regaining some more health at 35. And I imagined a Deal or No Deal type bargain. What might I ‘accept’ and be happy with so as to avoid a worse fate?

Mostly, I settled on the idea that I would be okay if I wasn’t stuck with severe chronic fatigue, lying in the dark unable to do anything. If I could handle some mental activity, communicate in a limited way with friends, and do about a couple of hours of work per day, then I reckoned that would be enough. That would still have enough purpose and meaning that I could be satisfied.

The meaning that I have for myself is what I started this essay with: doing work to try and make society better, and in particular, my legal theory work. There are many different whys and meanings to be found in life. Meaningful relationships, helping others, grand ambitions, and so on. For me, this political work has always been the highest one, though I also find lots of meaning in helping others, whether through coaching parkour or caring for others. Not having children or a significant life partner, loving and caring for them isn’t a purpose that drives me, and I was and am well aware that both of these things become much less likely if one is severely ill. I hope that I might be able to do some form of teaching and/or care work, even if incapacitated; I had previously thought that I might be an old man unable to take part in sports but still able to mentor and coach. But the primary thing was my work.

5. Grief and Letting Go

This writing process has been a bit strange. In the previous section, I tried to capture the thoughts that I was having in the depths of the crash in December/January, from some scrappy notes I made in February. What follows is an extension of those thoughts and my first few months of this year, but written months later.

Once I had a dream

Once I had a hope

That was yesterday

Not so long agoLyrics from ‘If I Had a Boat’ by James Vincent McMorrow

In the months since, despite this core essence of acceptance that I discovered or developed, I have still been grieving. It’s a strange process, of course, not always one that’s easy to describe either. In January and February, I did not make a quick recovery. I seemed to be at about the same level as at the start of January – out of the horrible depths, but barely able to do anything physical or mental. With this it was apparent that I would not be able to be financially independent and living in London.

By March, I was just about able to do two hours of work on a good day, and otherwise pass the time with an easy video or audiobook. In May, my parents went on holiday for a week, I felt like I would be capable of going to the kitchen and back to get food from the fridge, and while the first two days felt fine, on the third and fourth I crashed. This is the strange aspect of the condition where I feel fine at the time, not crossing a shallow/immediate threshold, but it’s still too much in some deeper down way.

From there, it was clear that I could not live independently and feed myself – if prepared food is available I can eat it, but I can’t prepare anything. On my own I would eat canned fish or already cooked meat with oat cakes, or a ‘just add boiling water’ dish (such as Huel, who strangely seem to focus their advertising on active professionals instead of cripples…); I usually wouldn’t even microwave it. In June, they again went on holiday, but this time with a fridge upstairs I could access, I was able to take ready-to-eat meals out of the fridge and eat them cold without crashing. I again set myself up on the landing, so that food and bathroom were in close proximity, and I only went to the bedroom to sleep. I was able to survive solo for a week, but still quite some way from physical independence.

The grief/acceptance flow is funny. On the one hand, I am (just about) above what I had hoped for in the depths of my crash. On the other, the sadness and grief hasn’t magically disappeared.

Thankfully, I am able to do some work. I can do two hours of work per day, on good days, and pass the time with an audiobook or easy videos on the afternoon. I can talk for a few minutes occasionally. My PhD is on pause, and I have been doing one day per week with LFN. What the future holds for my work is uncertain, whether I remain stable at this state or my capacity increases. I am also aware that my work is in the ‘ideas’ space and that the world moves on, and I won’t be able to keep up with it. For example, I used to be current with politics, and now I’m not.

So, I am able to do some of my meaningful work. This is great. I don’t live in daily hell. It’s not easy, I have to be careful, sometimes I have crashes, but it’s okay.

Yet despite this core rock of acceptance formed in the crash, I am sometimes still grieving. Often, not as much as might be expected. Mostly, it comes down to not thinking about things. If I just exist in my bubble, day-to-day, then it’s ok. But when something comes up that reminds me of the difference between my life and how my life would otherwise have been, or how most of my peers live, then it’s quite sad.

I am well aware of the void in experience where most of my friends are living normal lives, with the normal stresses, and able to do things such as walk out of the house, play sports, see live music and socialise, all of these things which are unthinkable to me at the moment. I see friends only when they visit me, and even then I can’t talk much. I can write some messages, but am still limited and have to be careful. Many friendships have already drifted away, and will continue to do so. My life experience is much less relatable. When something crosses into my bubble – invited to a friend’s birthday celebration, or a work event I would otherwise have gone to, or something about sports that I would otherwise have done – I’m reminded. Even when friends visit, their presence in the room with me, mostly not talking, reminds me of how much I can’t talk and have normal interactions and relationships.

These things come as reminders that my life will be a lower quality of life than the trajectory I was previously on. It reminds me of a blogpost I read a few years ago, which included the line ‘accept a lower quality of life’. The author is an academic whose health gets worse, and they relay a story:

I remember a conversation with a friend once about a situation where a medication good at treating their particular condition was taken off the market, and the parents of a kid with the condition contacted my friend to ask how to advocate or find other ways to get more of the medication, and the friend had to keep saying no that wont’ work, no you can’t get it, no you really can’t get it, no your doctor can’t write a special note, until finally they asked directly, “So what do we do now?” to which my friend answered, “Accept a lower quality of life.” That phrase crystalized things for me. I think in many ways no ending is scarier for us in narrative than accept a lower quality of life. It isn’t a one-time tragedy like death, we have good narrative tools to write tragedy, and to transition focus to the characters who live on, commemorate, remember. Accept a lower quality of life in a story means losing, giving up, surrendering, all the things we want our brave and plucky characters to never do, and then having to live with every day being that much worse forever. It’s neither a happy ending nor a tragic ending, it’s a discouraging ending, and we rarely tell those stories.Ada Palmer/ExUrbe.com ‘Medical Leave Reflections plus Empathy Sphere Essay’, 8 October 2021

People often ask me what the doctor has said or what treatments are available. The 3 GPs I have seen knew less than I did about the condition. I have been referred to two specialist clinics; one was less than useless, giving bad advice; the other has been good. There are no good treatments, the condition is not well enough understood, there is no cure. Hopefully, in the future this will change, but it isn’t inevitable that a good treatment will be possible. Most people want to imagine a world in which we can be healed – either due to a mystical belief in medicine, or because people don’t want to accept living in a world where these things are outside our control. We like hero stories and people overcoming things. This is not a health condition that can be overcome. As the title of this book which looks good but I haven’t read says,

Some of us just fall.

As there was little recover in the first months of this year, I have to accept the reality that recovery is not necessarily what will happen. Perhaps before my first relapse, I might have been able to recover well, but accidentally overdoing too much set me back and disturbed the healing. Same before the second crash, though I was being careful not to overdo it, and it fell apart very suddenly. This is a chronic condition, and I might have it forever.

I watched the Lord of the Rings films over the last few months, and the ending hit differently this time:

This could either speak to Frodo’s grief and trauma, or it could be interpreted (both the quote and the film) that he has suffered a mortal wounds, and willingly takes the boat to the undying lands while still young. Either way, perhaps this thing won’t be mended with time, or if it is, I have to somehow pick up the threads of an old life and go on.

And Yet… Acceptance and letting go of comparisons

I wanted to redraft this as it loops back on the same things and repeats. But I didn’t have time. Simplifying it into that narrative of grief/acceptance doesn’t really work anyway, so if it’s repetitive and sub-standard writing, that does reflect the lived experience of it…

Shifting to ‘acceptance’ from the start was definitely useful (though it’s still an ongoing process). There has still been grief on the way, as I didn’t recover in ways I might have hoped, or reckoning with what has been lost. It is an ongoing process — after a few months when I realise I’m not recovering much, or now, in the summer, by which point I thought I would at least be able to do short walks outside and get out the house and meet friends… which I’m still a long way from. But the core of acceptance is good.

Because one of the big things is, why should I be comparing my fate to what could have been? Why does it make sense to compare to that alternative?

At some point as a teenager or young adult, I realised it was pointless to compare myself to others. I’m born with my body, with all of the circumstances outside my control. As an athlete, if someone else can run faster than me, why does that matter? All I can do is choose what to do. I stopped caring about winning or whether I was better than others, and focused on doing my best. Playing rugby, if I played well, even if my team lost, I had a good time. At university, I decided not to mind others were cleverer than me or got better results. I’m trying to do good in the world, not beat others.

I should recognise that I have been very lucky, in many ways. Aside from various physical health issues, my body seems to be naturally strong and tall, and my brain seems to be a fairly good one. I was among the best at school. I got on with people. It’s perhaps easier to be accepting of not being the strongest or cleverest when you’re in the fraction at the top, instead of somewhere in the middle or lower down. Though, ultimately, the principles are the same. In my career, I’ve had lots of lucky opportunities. It’s a blessing to be able to work on something I care about, instead of have to do work that isn’t meaningful as many have to. If my health recovers somewhat, I’m not in a bad place going forwards.

Anyway. For years, it was all about the focus on being the best version of myself. So it makes sense to compare myself to my potential, when that is what was driving me before. Accepting a health limitation, just like any external limit, is hard. It’s beyond our control.

Nonetheless. The core point is the same. It’s beyond your control. It is simply how it is. Let it go, accept it, and live with what we have.

At the same time, there’s some comparisons that can be made for gratitude. It’s a bit like a one-way diode: be grateful for what you do have; pay no attention to what you do not have.

These sorts of comparisons can be more useful. I could have been born in the past, where I would still have a fractured back [I had spine surgery when I was 15 after developing stress fractures] and not be able to do much. I might have developed cancer age 22. Or, in the time before modern medicine and higher material standards of living, I had a ¼ chance of dying in my first year. I could have been born in a different place, or to a different family. I could be in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, precision missiles raining down with no way to escape, or in Ukraine, forced to take up arms against an invader. Or any number of places with political and social issues, famine, ecological problems, and so on. Perhaps if I wasn’t at home ill I might have been unlucky on the roads and killed while cycling. Who knows.

And, given the health condition that I do have, I’m in a pretty good situation. I’m well looked after by my parents. Most days I am not suffering, just bored and frustrated and isolated. Food is brought to me, things are sorted for me, so I can just rest, work a bit, move to the bathroom and back, and pass the time. I don’t have to worry about domestic labour and figuring out how to arrange sort food and cleaning and so on while crippled without overdoing it. So, in those ways, I am in a blessed situation.

So, why compare? We know not what shall be on the morrow.

Reflections on nature and comparisons (again)

I wanted to revise this and make it fit better, but, there isn’t the time, so it’s a bit clunky. If you’re still reading I have no doubt it’s forgiven!

How about: it is good to let go of comparisons which are an attachment to something beyond our control; but good to keep comparisons that help us to be grateful for what we do have.

Attachment to the path I was on or the life I had takes too much for granted. This modern liberal belief we want to have about our agency, and the idea that we can choose who are and what we do in this life. The reality is, in nature, nothing can be taken for granted.

We live in a world of order and chaos. This is the mixture found in nature. In our individual lives, we move through flows of both sorts. Life as defined by Maturana and Varela, paraphrased, is an organism trying to create order for both its internal environment and its external environment, against a dynamic world of disorder (at least from the perspective of each organism). We have dreams for our lives, try to do things in the world, form relationships with people, achieve goals, against all sorts of chaotic flows which we have no control over.

In my first couple of months, I watched some other nature . I found myself feeling connection with other mammals who hibernate, spending months of the year just waiting and resting. Animals in winter who huddle against the cold, just as I was, with my problems with overheating meant I had to often be on the edge of being cold. 50% of polar bear cubs die in their first year. Prey animals who run free, yet at any moment might be struck by a predator. Butterflies huddled all around trees trying to survive in a winter forest, where a quarter of them will simply freeze to death.

I think of ant colonies putting effort into building cities and civilisations, yet can get destroyed easily enough. I think of places that have had huge floods, where everything just gets wiped out. I think about communities and societies who have been powerless against their destruction, whether from illness, famine, other animals, or other humans.

I lay at home, thinking of Palestinians being bombed in the thousands with no escape. Ukrainians fighting for their lives, or at home hoping they don’t get bombed. People who are having atrocities committed against them. People in situations where they have to fight for their freedom, political activists and prisoners the world over, who challenged the state, fossil fuel companies, gangs, the right wing, concentrated power, and so on. Including those in the UK sent to prison or who are attacked or subject to public campaigns against them. Beyond violence, people who experience drought, famine, sickness, poverty, etc. I currently can’t do much to join the struggle for freedom, to do good about the world, and I feel sad about that.

I lay there, feeling ill and sad, thinking about other humans suffering. All of us die, many of us experience traumatic events, those of us who live long enough will have many people and things to grieve. Is the default condition to suffer, to struggle for freedom and survival? Or is the default condition to be content, and suffering is just a countercurrent against this? It’s a nonsense question; there is no default. Simply, all aspects are present. At any rate, these comparisons help me to be grateful that — for the time being at least — I have somewhere safe to live, well cared for, with no worries about safety or hunger, without having to stress about doing domestic labour while not making myself more ill.

6. Ultimately

I guess what it comes down to is something like this. There are both positive and negative emotions in me. We can’t choose not to feel those things, but we can choose, to some degree, what we feed and what we cultivate. Sometimes emotions are overwhelming and we can’t consciously do much about it – the conscious brain is just one part of the mindbody, it’s not in charge of it. So, I do my best to try and cultivate gratitude, move forward with what I have, and let go of the grief. It’s ongoing — I cried yesterday about it, as it happens — but the process is much the same. Writing this has been part of that process, as well as mindfulness/meditation practices, and so on.

This is the same with everyone, whatever is going on. All we have control over is what we do, and to some degree, our mental attitude. That isn’t to say it is possible to overcome everything, or that people who fall apart didn’t try hard enough. It’s just to state that this is all that we have control over.

I had already worked to cultivate this attitude years ago, so taking the approach of going with the flow and accepting it as best I could was not too difficult when I first got ill. As a young adult, I made the decision to and live my life without regrets. To live knowing that life and time is previous and fragile. I’m glad that looking back on my 20s, there isn’t much I kick myself over. I chose to chase a passion instead of getting a stable job (and got lucky along the way). I tried near enough my best. I threw myself into parkour after recovering from the back surgery, because it looked fun and I wanted to make the most of physical ability. I’ve lived in another country, had an interesting job working in politics, ticked off some things I wanted to do and try. Hopefully there’s much more good stuff to come, but I’m glad I made the most of it all when I could.

It’s two-faced. One the one hand, thinking back on the more ‘normal’ part of my life until now, it feels like it might be over. On the other hand, instead of being too attached to the hope of recovery, I should accept whatever shall be and make the most of the present. it’s not over. This is my normal, and it’s a continuity of sorts.

In one sentence, it probably all boils down to this: I am currently alive. I should make the most of it. Make the most of each day, as best I am able.

As I’ve written about before:

Hopefully I can keep this attitude even if I become more ill, certainly it would be much harder to keep in the suffering of ‘conscious coma’ of severe chronic fatigue.

If God is a DJ, life is a dance floor

You get what you’re given it’s all how you use itP!nk – God is a DJ