To many, the result of the UK’s EU Referendum might be a shock. Here, I try to explain what I think happened. This is, of course, all going to be historical interpretation by me. Everything I present as fact I believe to be so and with sound evidential basis, even if I haven’t had the time to provide links to all of the substance or explain all of my points. The opinions and interpretations of history are that, but I (of course) think they are correct.

Sorry it’s long – I uploaded this right before going to the pub and didn’t have time to write a summary.* Well, a rather quick summary: there’s been a long anti-europe and anti-immigrant sentiment, the Leave campaign was pretty dodgy with lots of lies, the Remain campaign wasn’t much better and did little to persuade people of much, and it was fronted by the Conservative Party and David Cameron, themselves responsible for much of the anti-EU and anti-immigration sentiment. This limited their arguments to vague assertions about economic security, they never argued anything positive about the EU, or a vision, and it is no surprise that a great many ‘working class’ people didn’t like his arguments and that the anti-establishment we want change sentiment was captured by the Leave campaign, which was able to present itself as a revolution and give people actual power to change something, even if it was against their interests and for the wrong reasons.

*Or do a full proof-read, so apologies for the imperfections and that it isn’t finely crafted but a bit raw.

***

Political History (for context)

- 1973: the UK joined the EU (or at the time, EEC). It had been wanting to join for a decade, but a French politician kept vetoing it. After that politician retired, the UK joined. There was no referendum to join, referenda are (or were) quite rare in the UK – rather, it was done by the government of the day, a conservative one.

- 1975: the UK had a referendum on whether to stay in the EU. The referendum was a campaign pledge of the Labour leader as part of their general election campaign. Labour won the election and so held a referendum, in which 67% voted to stay in.

- (skip a bit of time)

- 1997 until 2010: the Labour party was in power with Tony Blair as the leader. They won in 1997, again in 2001 and again in 2005. Typically, parliament lasts for a maximum of five years, but the prime minister can choose to call one sooner. This was ‘New Labour’, Tony Blair’s vision of a modern labour party: in effect, it shifted towards the right. Margaret Thatcher, Conservative Prime Minister in the late 70s and 80s, once said that Tony Blair was her biggest legacy. Tony Blair stepped down as leader, passing it onto Gordon Brown (who had been Chancellor of the Exchequer, aka Treasury Minister).

- 2010: a general election happened, and it ended up with a coalition government of the Conservative Party and Liberal Democrat party. David Cameron, leader of the Conservative party, a (relatively) young and charming man, became Prime Minister.

Since WW2, the UK had a two-party system between Labour and Conservative (not dissimilar to the USA), with a few small parties holding a small number of seats. The Lib-Dems (the common abbreviation) had around 50-60 seats (out of a total ~650). Post-WW2, this was their first time in power, and also the first coalition government. The dominant policy was ‘Austerity’, which meant cutting public spending. They claimed that this was to try and cut the budget deficit, but actually made it much worse. Austerity has never made any actual sense as an economic policy and was purely political. Throughout (and to this day), the conservative party blamed ‘Labour overspending’ pre-2010 for our economic woes, which was again without basis but widely accepted. - 2011: the AV Referendum happened, about whether to make a small adjustment to our voting system allowing people to rank preferences in their constituency. This was promised as part of the coalition agreement, the Lib-Dems wanted it, Labour and Conservative did not. It was almost certainly a better system (not good enough though), and would favour smaller parties instead of the big ones. Unfortunately, the Lib-Dems had crashed in popularity in their first year in the coalition, as they betrayed many of the promises, most notably in allowing for tuition fees to rise from £3k to £9k. So the voting reform was rejected.

- 2014: Scotland had a referendum on whether to be independent. The Scottish National Party (which had some support in Scotland) had wanted this for awhile. Scotland voted 55% to stay, 45% to leave.

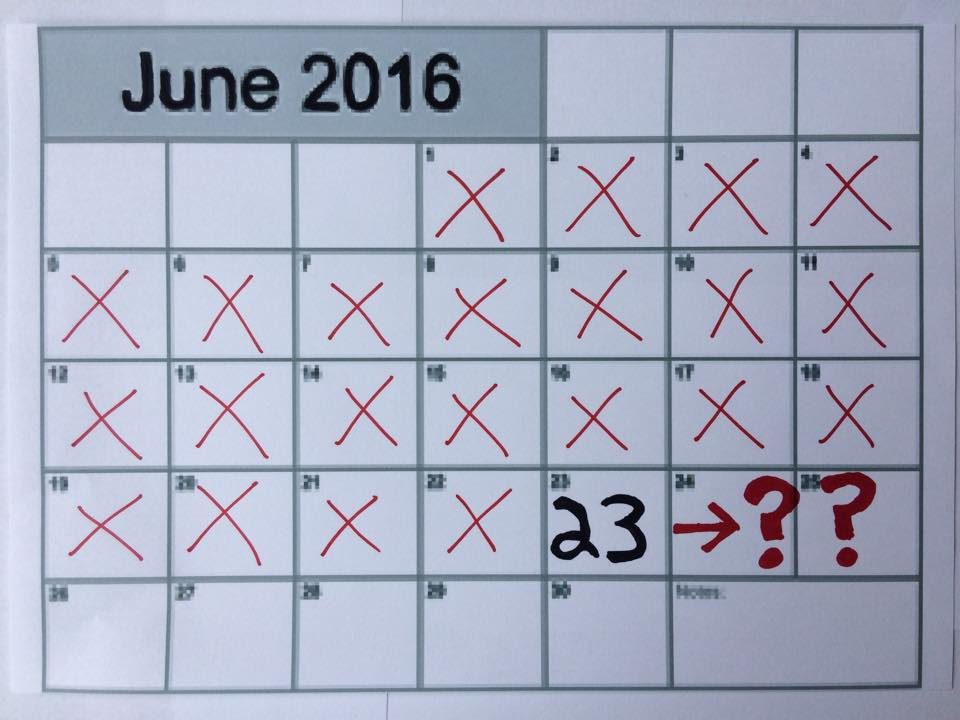

- 2015: a general election happened. The Conservative Party won outright, though with only a small majority (~20 seats or so), so David Cameron stayed Prime Minister. One of their manifesto pledges was to hold a referendum on the EU before 2017, and earlier this year it was announced to be on June 23rd 2016.

- The Labour party had contested the election with their new leader Ed Miliband, but they had been quite weak in opposition. They remained ‘New Labour’ and didn’t actually differ much on policy: they said that they would make the same budget cuts that the Conservatives had promised. The media narrative was that the Labour party had been viewed as

- Later in 2015, the Labour party had a vote on who its new leader would be. Jeremy Corbyn, a long-standing and principled socialist who had been an MP for decades but had never been important in the party because he did not support New Labour’s neoliberal agenda, was elected with a huge majority (59% of the votes). The vote was from the members of the Labour party (around 400,000 people), and he did not have the support of the ‘Parliamentary Labour Party’ – the elected MPs of the Labour party. Throughout and since his campaign, the media (and Conservative party) has been very strongly against him, and a minority of MPs have continued to drag their heels and oppose him (much more than they’ve actually opposed the government). This has sparked again with a call by a few MPs to vote on whether he should remain leader, in light of the EU referendum result: they claim he didn’t do enough to campaign for it.

UK Anti-Immigration Sentiment, 2010-2015.

The UK, being an island, has been a bit funny about Europe for as long as I’ve been aware. We refer to the mainland continent as ‘Europe’, in a way that suggests we aren’t ourselves part of it. Britain has never really felt very ‘European’.

There’s also a history of blaming the EU for bad policies, even when the UK supported them. This works because the Council of Ministers (and Council of Europe) – who have lots of the power of what to do with the EU – have all of their things in secret, so there’s no accountability for what they do.

The Conservative Party, in power since 2010, has had a strongly anti-immigration rhetoric. They promised to ‘get the numbers down’, which was a bit of a problem because 1) lots of the immigration was from the EU, which they could not control, and 2) immigration is actually very important to the UK, with lots of key jobs (especially in healthcare) being done by immigration. The NHS, for example, would not function without immigrants.

I see this as a scapegoat strategy. The 2008 financial crash caused some damage, subsequent recession and economic woes. The Conservative Party then continued with their ‘Austerity’ agenda, cutting budgets all over the place. Many more people have started using foodbanks (charities who give out food for free for people who don’t have food), homelessness has drastically increased, and so on. The Prime Minister himself – in his role as local MP, representing his constituents – actually wrote to Oxfordshire County Council complaining at their cuts to services: elderly care, libraries and museums, childrens centres, homelessness funding. As well as this, there is a huge economic inequality due to the economic structure of society: some might argue capitalism inevitably leads to greater inequality, but certainly the current structure has done so.

Yet the Conservative party, instead of facing any to this reality, instead blamed immigration. I’m not really sure what his reasoning for this was – I had a look through a 2011 speech and it was just along the lines of ‘there’s too many people for our country/cities/etc’. They set targets of net migration, and failed to meet them year-on-year. They talked about ‘economic migrants’, as if we had such a wonderful welfare system that people would move here just to claim benefits (which they could never do, because our system isn’t actually just free cash and requires you to actually be looking for a job, plus if you had migrated here you couldn’t claim for a few years anyway). They talked up ‘sham marriages’ and so on. They had a strong anti-refugee policy, supporting the EU’s anti-refugee policies and, on the more recent Syria issue, they pledged to accept 20,000 Syrian children before 2020, but on the condition that they would be returned once they reached age 18.

This meant that the anti-immigrant, xenophobic and racist rhetoric grew. This was also strongly fueled by the press: for many, many years there have been anti-immigrant stories, often misleading, in many cases flat-out lies. The UKIP – United Kingdom Independence Party – grew in popularity. They had no real chance at getting into Parliament, because of our voting system requiring a majority in the constituency to get a seat, but they got 27% of the vote in the 2014 elections for the European Parliament. The Conservative party carried on drifting to the right, to keep support of people it had been pushing there.

In 2011, the Conservative Party also made a new law which said that any future transfer of more power to the EU (which means a new treaty) would have to be supported by a referendum. This is novel and posed an interesting question to law students like me, as the UK does not have a constitution, which meant that there was nothing actually binding about this law as such: it meant that the government couldn’t sign up to a new treaty itself, but the parliament could repeal the law no problem.

During this time, the Labour party was somewhat mute in opposition. As I said above, they didn’t really have different policies for the 2015 general election, as they had shifted to the right under Blair’s New Labour. They were never pro-immigration. (Of course, everyone would be pay homage to immigrants, talked about the benefits and the doctors, but not actually be pro-immigration).

So the Conservative Party, in 2015, perhaps realising that they were somewhat weak and that if their vote was taken by UKIP they would lose lots of seats, promised that there would be a referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU. David Cameron did this in order both to appease some of the Conservative party, which contained some anti-EU MPs, and also to voters. He always said that he was strongly for staying in, and he was. It is now obvious that he strongly misunderstood how ordinary people (he is certainly not one, having been privately educated and stayed in a particular social group his whole life) thought.

Given what’s happened, it’s quite nice at least that it’s the end of David Cameron’s career, given that he is responsible for much of the anti-immigration sentiment and the decision to hold a referendum (which was unforced).

The Press

As an example, here is a page of front-covers from The Daily Mail, which is the most-read newspaper in the UK. Owned by a billionaire who lives abroad to avoid tax, by the way – not that it stops them criticising others for the same, or calling political figures unpatriotic, or so on…

And in many cases, they publish stories that are somewhere on the spectrum of whoops-slightly-misleading to obviously-a-lie.

<https://infacts.org/mail-online-corrects-inaccurate-nhs-migrant-story/>

Unfortunately, the press regulator is quite weak. There was a big inquiry, the Leveson inquiry, which made stronger recommendations about having a better regulator… but the media, which in the UK has very concentrated power among a few rich owners and a lot of influence and close relationships with certain politicians, didn’t want this, and there was insufficient political will to do anything.

The Leave Campaign

The Leave campaign has been a bit of a strange one. It has had a few particular figureheads, but pretty much no support by politicians, political parties, or experts of any kind. All political parties, including the Conservatives, wanted to stay in the EU: there was a minority of Conservative MPs (70-100, around 30%) who wanted to leave, and about 10 Labour ones too. So it was instead led by a few personalities: Nigel Farage, who was pretty much the entirety of UKIP and had been appearing on various TV shows for a long time; Boris Johnson, who was mayor of London until last month, and had previously been pro-EU (many view his choice as being a political one about gaining power in the party, perhaps to be a future leader); and a couple of Cabinet Ministers who had been in government since 2010 (Chris Grayling and Michael Gove being the main ones).

And backed up, of course, by a right-wing anti-immigrant anti-EU press.

There were three main strands to arguments by the Leave Campaign.

1. Sovereignty.

They changed this later to the slogan of ‘Take Back Control’, which has much better popular appeal. What they mean is that they want UK laws to be made by the UK, not by the EU. This argument never acknowledged that 1) we actually have sovereignty, we haven’t given that up, because it is within our power to make contradictory laws or leave, so what they mean is ‘political power’, and 2) that we make a trade of the EU making laws over us in return for us having influence into EU laws, which cover other countries too.

This argument, and all of the ‘eurosceptic’ (anti-EU) coverage, almost always refered to the EU as ‘unelected bureaucrats’ – meaning the European Commission, the equivalent of the Civil Service, who are indeed unelected bureaucrats, but entirely ignoring the fact that the actual policies and laws come from the Council of Ministers (1 representative per Member State), the Council of Europe (where the heads of state of each Member State meet every half year or so to decide general policy direction), and the European Parliament, which contains directly elected representatives from each country. The argument was not made that ‘we only have a small influence because were are one of 28 countries’, nor was it made that the policies we wanted were different to the rest of the EU and that we were always outvoted (which is not the case). It was almost always about ‘unelected officials’.

The campaign and the media also conflated between the European Court of Justice (the EU court, and EU law) and the European Court of Human Rights. The Conservatives and much of the media is against human rights (they want to repeal the human rights act and unsign from the European Convention of Human Rights, and replace it with a British Bill of Rights; the only reason for this is to give weaker human rights protection, because it is fully within their power to give greater human rights protections at present). The two examples they really hate are prisoner votes – as the ECtHR has said that our current system is in breach of the right to vote – and the fact that human rights have been extended to people killed by British armed forces in Iraq. They also misrepresent these as being against our sovereignty – which they are not, because UK law does not require us to follow the decisions, and prisoners remain without the vote, despite it being 8 years since the first ruling on this.

2. Immigration

Like I said above, there is a strong anti-immigrant sentiment, and this was a huge part of the Leave campaign. It was described as out of control, that we are full, that we needed to control our borders, etc. There wasn’t an economic basis for this, nothing giving any reason for it, at least that I ever saw.

Of course, they never said they were against immigration as such… just that they wanted controlled immigration, and not the EU free movement. In recent times they started to talk about an ‘Australian-style points-based system’, which gives points based on various factors as to whether somebody is allowed in. The Conservatives have, since 2010, been trying to lower (net) immigration to around 100,000 people per year, which has included various policies (for non-EU citizens) such as requiring a certain family income before somebody is allowed in. They have failed to ‘control’ immigration and meet their own targets.

Again, there wasn’t much evidential basis for this, or examples of immigration that would be cut or of policies they would have. Just a general sentiment.

Part of this campaigning also included fear-mongering about other countries, especially Turkey, wanting to join the EU. Turkey, of course, is brown-skinned and muslim: definitely not like us! The mention of Turkey rarely mentioned that this was not anything immediate, had been under negotiation for a long time already with Turkey nowhere close to joining, or that the UK would have a veto (as any country would) against whether Turkey could join…

3. Cost

The figure that kept being used was that the UK pays £350m per week (so around £15bn per year) to the EU. This was usually paired with an example of how many nurses, doctors, hospitals or schools this could fund. Could fund. The idea was – as with sovereignty – that we should decide how to spend this ourselves.

Again, it was misleading. It was never put in context, of being a bit less than 1% of national GDP (or 3% of the budget). It was factually incorrect: the real figure was £248m per week. It was also misleading in that it didn’t take into account the money we get back as funding from the EU: the net outgoings UK->EU was actually £136m per week. So a rational analysis would look more like: “we pay £248m per week, get about £110m back as funding that we don’t directly control, and get other EU benefits in return for the remaining £136m per week”.

There was also great discussion about what we could spend this money on. Except that all of the Leave campaigners were for austerity and against the principle of the NHS (Boris, Nigel and Michael Gove all having expressly said as much at various points). So somewhat deceitful that they said this. Nigel Farage backtracked a bit today by saying that the money would not actually be spent on the NHS, just that we would have a bit more money which we could spend on whatever he wanted.

Evaluation

So it’s technically correct that it costs some money, and that we lose some control over the laws (in the above-mentioned trade), and it’s correct that there is more immigration that we cannot control from EU free movement. Yet the sovereignty and cost points were presented in this grossly misleading manner, by presenting the EU as ‘unelected officials’ and ignoring the fact that we have a say in how it is run, and with the cost figure dodginess. These are both misleading enough to be called LIES: if you made these in another context, in a contractual negotiation or as defamation against someone, then that would be a crime. But in political campaigning, you can say what you want without repercussion.

There was also a lot of ignorance about the EU: most people don’t know much about how it actually functions; or immigration or cost etc. For example, the study linked to below concluded that “There are obviously still high levels of ignorance about the EU”.

I don’t mean to say that there are no legitimate arguments or that everyone who voted Leave is an idiot. What I am saying is that the campaign varied from vaguely correct but unsubstantiated claims to flat-out lies, and that most people voted based on reasons or views I think were factually misunderstood or otherwise illegitimate. I do not think the EU is perfect: it’s not very democratic (mostly due to the Council of Ministers being done all in secret, which is by design because governments didn’t actually want to give up their power, so that serves the EU right as without that I think the result would have been different); I don’t think a single currency is a good idea; their treatment of Greece and disregard for greek democracy was terrible; and the anti-refugee policies are dire. It could be a legitimate view to think that the UK is better off alone, for people to have principled reasons about governance and so on – what I mean is that the Leave campaign did not make this in a legitimate argument.

(And, to be fair, the Remain argument was also terrible: I did not think that legitimate or particularly good either, I voted remain for my own reasons).

There were also a small number of ‘Left-Leavers’ – left-wingers who voted to leave. I think they are very mistaken, but this could be legitimate too. I think it fails on pragmatic grounds: outside the EU, there is much more right-wing control by the Conservative party (and UKIP), whereas the laws and policies made by the EU tended to be better. We look set to lose human rights, workers’ rights, and environmental protections, among other things.

What Did the Leave Campaign say would happen?

There was never a clear Plan Leave made, more vague assertions about us being able to go it alone, regain control, be stronger, and negotiate our own free trade agreements – and like I said above, spend the money we pay into the EU on our own things (ha!). There was huge uncertainty about this.

Much was made about Norway and Switzerland, who are outside the EU but still part of the free trade (and free movement and refugee accepting) deals. Of course, this was usually made without pointing out that they still pay into the EU, don’t have any influence over EU law, and have to accept some of these policies.

Why Did People Vote to Leave/Why Did the Remain Campaign Fail? (or, Why I think it happened)

On the most part, they were persuaded by the arguments, and unpersuaded by the Remain campaign.

It was able to harness a huge anti-establishment sentiment: those people who are not as well-off, (mostly) white, British working classes. The northern areas of England voted strongly to Leave, and they are economically poorer areas. The Labour party is being blamed for not doing more, and perhaps there is truth to that – I haven’t looked much into these – but the working-class media is mostly right-wing and not with the labour party (the newspapers The Daily Mail, The Sun and The Express were all right-wing, and only The Mirror is more left-wing – these are the newspapers these people might read).

David Cameron headed up the Remain campaign: he is not popular among these people and regions. He is pro-austerity, has cut taxes for the rich and generally (though not solely) put forward policies that disproportionately affect poorer people, such as attacking benefits (including in-work benefits for when wages aren’t enough, Universal Tax Credits), not providing affordable housing, and cutting public services. The campaign was dubbed ‘Project Fear’, as it usually did little more than vague assertions about ‘better economy’ and ‘better jobs’ if we remained, and talked about the danger and uncertainty of us leaving.

There was little in the way of positive narrative for the EU: David Cameron was limited by the fact he was anti-immigration and neoliberal, so he couldn’t argue much for a positive vision of Europe, unity and love and togetherness. He is also not a fan of human rights or workers’ rights or protecting the environment, so couldn’t make these arguments.

There was also, to some degree, a failure of ‘the left-wing’ to produce positive alternative arguments. Labour got involved more towards the end, and the Green party also made efforts (but they never get media coverage). This is not just an immediate failure though: Labour also did little about pro-EU or in countering anti-immigration sentiment in the past decade. Labour, until Corbyn in 2015, was also neoliberal, stopped calling itself socialist, and had generally centre-right policies (especially Ed Miliband in opposition, 2010-2015). The bigger problems, of austerity politics (as I’ve said, not based on sound economic theory) and blaming the ‘previous Labour government’ for over-spending (again, not actually evidenced), were not tackled until Corbyn became leader of the Labour Party (and almost the whole media has been against him, giving hardly any positive coverage).

So, given the general trend over the last ten decades, the negative way that the campaign was run, that it was headed up by the Conservative party (for the most part), the lack of proper challenging of the Leave campaign’s lies (which was politically difficult for Cameron, as they were almost all his own party members), and the way that anti-establishment sentiment was adopted by the Leave campaign, it isn’t particular surprising. This, of course, could be said to be the benefit of hindsight – but I have been worried and aware of many of these things for awhile (for example, THIS BLOG POST (be vigilant).

What Now?

A huge mess and uncertainty.

This is not a post about the future, but David Cameron has said he will resign in a few months, so the Conservative Party will need a new leader. Boris Johnson is a frontrunner, and other potential candidates are not very popular. It should be a weaker party.

Jeremy Corbyn, Labour-party leader, will also face further challenges around the claim that he and his party did not do enough. This is nothing new, he has been critised unrelentingly by the media and the older-Blairite-MPs have campaigned against him even more than they have against any actual government policy (or for the EU). A couple of these MPs have called for a vote of no confidence in him, which doesn’t have any basis – but will shake it. This is in the Parliamentary Labour Party – the MPs themselves – and not in the broader Labour Party (which gave Corbyn a landslide majority, 59%, next candidate around 19%, in the 2015 leadership election).

UKIP will be strengthened by this – they already had some strong popular support, but no parliamentary power with only 2 MPs. They may well campaign for electoral reform, which would take seats away from the Conservatives (mostly) and some from Labour, plus give the Green party a slightly better return.

The Human Rights Act is even more likely to be abolished – this has been policy for a few years but they’ve been unable to produce an actual policy on it – and the UK may even unsign from the European Convention of Human Rights (which was recently stated as an aim).

The Scottish National Party – which has nearly all of the MPs from Scotland now (prior to 2015, it was mostly Labour with some SNP – the SNP was a better socialist party, the Labour party was weak, and the pro-independence-sentiment did not actually increase during the time) – has called for a second referendum on independece. Scotland voted majority to Remain in the EU, and they don’t want to be dragged out by the UK, and this is a change in circumstance from the previous referendum.

There has also been talk about Northern Ireland, which also voted Remain on the whole, rejoining with the Republic of Ireland. I don’t know much about that.

The UK won’t actually leave for at least 2 years, so there will be some negotiation about what it will look like afterwards. This is under ‘Article 50’, which we will hear a lot about. It’ll be very messy in the UK, both politically (see above!), with the main parties being shaken up, the fact that it might just become England and Wales (which was only ever one Kingdom, Scotland was the second one that united!), and also legally: the UK does not have a constitution, and there are now 40 years of EU law woven into ours, which will be a complete mess to try and untangle.

As for the implications on the wider EU, who knows what that might be… I would say the EU is looking fragile, I have thought for the last year or so that it might collapse in the next 5-10 years anyway, what with the issues regarding sovereign debt (Greece, Spain, Portugal, Greece) and so-called ‘refugee crisis’ bringing tensions right to the front. The UK’s Leave vote is the third big weakening event.