Note: This post is a bit raw. Usually, I would write something in draft, then come back and redraft and edit it. Usually that means some changes, making sentences smoother and the whole thing flow better. On this occasion, I wrote this whole post in one go and have published it without redrafting or editing. I am also aware that at times, I make statements about how the world is without providing supporting links. While I would like to be able to go through and provide full explanations and links for things – as well as redraft and edit – these things take time. I decided to put this post out there as it is, especially given the current date, and I have other things I’d like to do with my time – it is just a hobby blog after all! However, everything I write here I believe to be true and reasonable and with evidence to back it up – feel free to comment and ask for any of it, and I’ll do my best to reply to that and provide evidence/substance (or, if I can’t, edit and remove a point).

And yes, it’s long. Like I said, I could edit to be a bit more concise, but the length is due to substance, further discussion of what Black Swans are (sections 2 and 3) and the political context and the media (section 4). If you want a quick read that is just about the post-EU-ref world, read the Introduction, then section 5 and the conclusion.

*** 1. Introduction ***

The EU referendum is huge. Not just the vote itself – and the decision of remaining in the EU or leaving it is a big one – but also whatever happens afterwards, either way. If we vote to remain, we won’t go back to ‘business as usual’: we will go forward to a post-EU-ref world. If you’re in a relationship with someone and make some big mistakes, even if they choose to stay with you, the big mistakes are still something that happened and form a part of the relationship going forwards. It will be a huge change.

In this sense, the EU referendum is part of a cluster of Black Swan events: events that are outside what is generally being considered. This blog post discusses the theory of black swan events and talks a bit about what might happen after the EU referendum.

*** 2. Black Swans and Nassim Taleb ***

For a long time, people thought that all swans were white. They only saw white swans, so they assumed all swans were white. But then it turned out, black swans did exist. Inductive reasoning can never be 100%: inductive reasoning is when you observe lots of things, then make a general theory on it. Science works like this: you do experiments and then make theories based on it. Scientifically, people thought that swans were white: 100% of the ones they had seen were. But this can be fallible: the general theory is only as strong as the base it comes from. Perhaps all swans in all villages in England were white, but they hadn’t included swans in other countries.

The same works for less-scientific theories. One comes on judging how nice people are: if you judge people only by how they treat you, you are missing a lot of the picture. We, naïve and optimistic humans, often assume people are nice when we are starting out as friends or in business. Yet we would only actually be basing our judgment on how nice they are to us, how nice they are when making a first impression or when they want something. Instead, if you want to see how nice people actually are, look to how they treat people they do not like: in the past, the saying was how they treat their servants. Then you have a more complete body of knowledge to base your judgement on.

The concept of ‘Black Swan events’, which are named after the black swan example described above, was introduced to our societal awareness by Nassim Taleb. Not fully introduced, but many in business, finance and ‘risk markets’ are aware. He argued (and he is right!) that most of our approach to risk and strategy is flawed, because we base it only on what we predict. One example he gave was at an AGM for a big car company: they predicted their profits over the next five years. He pointed out that they have made a similar prediction five years before and been completely wrong – so why did they trust their prediction again? Another example he gives is ‘turkeys voting for Christmas’: the turkey is well treated, fed and cared for (the reality of their horrible battery conditions aside), and sees everyone getting ready for a party. Sounds good to the turkey – but the turkey doesn’t realise that it’s on the menu. To the turkey, that’s a ‘black swan event’ of sorts: it does not see it.

For a slight tangent to complete the Taleb point. Taleb has written a number of books. He started with Fooled by Randomness, which (I haven’t read but) is something about stats and how people misunderstand them, where lots of randomness is treated as actual information. His second book is about Black Swan Events, discussed above and below. The third/fourth one (there was one inbetween that was more about practical application than developing his theoretical approach) was called Antifragility. In that he says: given that there’s all of this randomness that we can’t predict and that Black Swan Events are what actually make change, how can we respond to that? The answer is to focus on how fragile (or not) you are. If you are fragile, even if you are very efficient at what you do, then if the situation changes, you are ruined. The banking industry was likely reporting huge profits in the years before the crash – they thought it was going great! He develops a concept of antifragility, which I won’t talk more about here, but I have mentioned in this blog post (where I discuss the book and highly recommend reading it).

*** 3. Black Swan Events and History ***

So, Black Swan Events. Most of the big changes in history come from unforeseen things. If it’s foreseen, it is expected, so doesn’t always change much.

A week before World War I kicked off, nobody was expecting a world war. They all thought that it was just a minor diplomatic (or family, given that the leaders of Britain, Russia and Germany were all cousins) squabble.

Before the financial crash, nobody expected a financial crash. Well, a few people had realised that the whole system was very dangerous (including Taleb – his book on Black Swans was published before the collapse, and he’s credited with having semi-predicted it), but the majority hadn’t twigged.

The end of the cold war (though arguably it’s continued, what with Nato and continued imperialist USA foreign policy) and the fall of the Berlin Wall also came out of the blue. Sure, it could be seen that there was rising discontent across much of the Eastern Bloc and protests in many countries in the period, but that had been true at many times from 1950-1990. There had been protests in Berlin, but nothing particularly unusual. Two days before the wall came down, it was not expected to come down: then the East German government announced that it would reduce travel restrictions, and during a live press conference somebody asked when this would happen, and the government representative (who didn’t really know what to say), said something like ‘immediately, I guess’. Suddenly thousands turned up at a checkpoint through to West Berlin, and at one point ten people at the front surged a bit, the guards made a split-second decision not to start shooting everyone, and then hundreds ran through. This turned into a huge protest-party and people started demolishing the wall. This was the flashpoint of the USSR collapse – unforeseen.

The development of technological advance is like this too. Even after computers had been developed, the top people didn’t think that household computers were going to be anything more than niche. Similar with the internet: it was not realised how revolutionary that was going to be. Same with the printing press. I think we are currently in the same situation with regard to AI technology: we are on the cusp of an AI revolution, with HUGE potential, yet the ‘mainstream’ of politics and business hasn’t reacted.

*** 4. Recent Political Events and The Media ***

Moving to political events and the EU referendum, so much of what happens is ‘unforeseen’. When Jeremy Corbyn was nominated to run in the Labour party’s leadership election, he only just got enough nominations to be in it and was put in just to add diversity to the campaign (by having an actually left-wing/socialist candidate, the other three being on the right-side of the Labour party in the style of Blair). At that point, absolutely nobody was predicting he might have any success. As the campaign developed, it became somewhat apparent that he was doing well in the way he was drawing crowds to his speeches, but the general media continued to dismiss him as an outsider. At some point, it was realised he had a big change – at which point the media went on the offensive, smearing him as much as possible, calling him dangerous and ‘unelectable’ and so on. This happened with some classic media doublethink: describing him as simultaneously having no chance while warning us how dangerous he was and not to vote for him.

The same happened with Bernie Sanders’ campaign for the democratic nomination – and also for Donald Trump’s, as it happened. Nobody thought he would have much chance, he was nearly unheard of and running against a ‘clear frontrunner’. Yet as the campaign progressed and more people heard of him, he gained ground.

Why are we so bad at predicting things? Huge question, I’ll give a couple of ideas for a brief answer.

One is that as humans, we have huge psychological blind-spots with things like ‘what we don’t know’. We assess things based on what we do know, even if that isn’t much, and don’t realise we are doing it. I know I do this, giving strong, confident opinions on things I don’t know much about (though now I’m aware of this blind-spot, I’m much better at quashing the impulse to do it). So when predicting the future, we do not take into account things outside what we know: whether that is a known thing (like the fact that Corbyn is running), or a thing nobody is thinking of at all.

A second is the way the media works.

The media is part of the establishment: again not saying much here, big media companies are huge corporations. Power crystallises. The politicians, big business, and the media all have huge shared interests: the media relies on advertising for its money, news is their output, but their business is in having an audience so that they sell advertising space to business. Politicians have close links to business, partly because of their ideology of how society ought work (that the state exists to make a stable place for business to operate because that’s good for the whole society), and because business wants access to power. There is also media interest in working with each of these: they need stories! If somebody – politician or business – puts out a press release, the media wants to publish it to get a story out. If the media start being too critical, either of politicians or of business, then they will stop getting the stories.

So anyway, big media companies are part of the establishment. They also tend to have the same ideologies and viewpoints: a big ‘groupthink’ or ‘silo effect’. So there are huge limitations to what they think. In the Corbyn campaign – and since he has become leader of the Labour party – the media was strongly against him. Despite his clear popular support – not just among the Labour party members but more widely – the huge majority was hostile. Similarly, there was little difference in the way that the media dealt with the decision as to whether to get involved in air strikes in Syria (strongly pro-war and madly in love with Hilary Benn’s speech **), and there is not really much in the media talking about the huge crisis of environmental destruction were are in.

So the media is stuck in this groupthink silo and not really very good at talking points outside the box. Much more like an echo chamber than any real diversity.

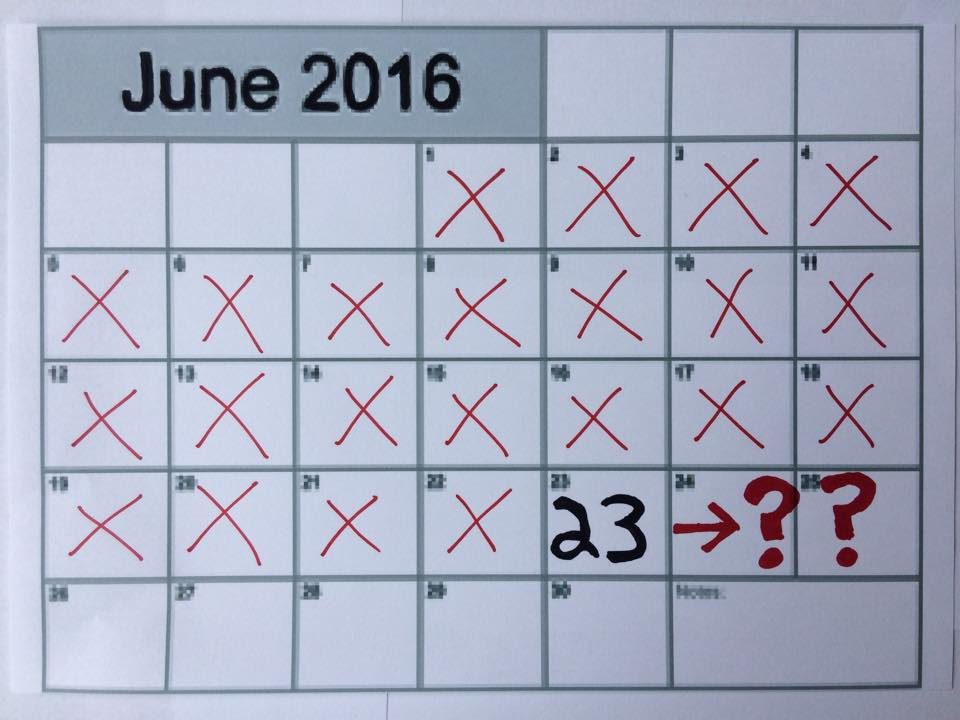

*** 5. The EU Referendum as a Black Swan Event and The World After June 23rd ***

Now to talk about the EU referendum as a black swan event. We all knew it was coming, and there is a lot of discussion about how important it is, but there is hardly anything talking about what comes afterwards. That’s what this blog post is doing.

Cameron might be out. There has been some discussion about this – more recently, even Dimbleby has challenged him about this: if the vote is Leave, or if it’s quite close, then Cameron should probably resign. It was he who decided to promise a referendum (presumably as a strategy to get more Eurosceptic votes in the last election), even though in the 2010 campaign all they promised was a referendum before more power was given to the EU. It was he who led a ‘renegotiation’ (which was never anything big, mostly about a made-up problem of EU-migrants claiming benefits, which was already quite limited!) which went nowhere. Even more than that, there’s been a huge schism in the Conservative party, with some of the cabinet splitting off to campaign for Leave. There has been lots of backbench anger about the fighting between parts of the party, branding each other liers and so on. They only have a small majority in parliament anyway, so it wouldn’t take much.

So Cameron is certainly much weaker than he was, with an unhappy and split party. (Somehow this got nowhere near as much attention as the comparatively minor infighting in the Labour party…). Whether he leaves or not, that’s a weak party. And they have not had a good year: despite their majority and without a coalition partner to restrain them, they’ve been pretty poor at actually getting things done, with many U-Turns. The thing with Tax Credits and Ian Duncan-Smith resigning; a failure to do anything more about abolishing the Human Rights Act, the education policy about Academies which contained a U-Turn, and a few others.

If he’s out, who replaces him? Osbourne is not popular and has none of the charm that Cameron has – he’s also been weak recently at turning up to debates about the economy or his budget. Theresa May is similar, but not as bad. Boris Johnson perhaps – though that depends how the vote goes.

There is a good chance that the Conservative Party is about to suffer a collapse: if the Leave campaign wins, this is even more likely.

There has been some discussion of this, with comments from the Labour party that they are ready for a general election.

We also have the Scottish independence issue up in the air: if the UK votes leave but Scotland votes to stay, that would probably be enough to demand another referendum on secession. The previous referendum was VERY CLOSE, and if membership of the EU is part of leaving the UK that could tip it.

What about the EU itself? Let us not forget, the EU is novel and unprecedented. We have had the most peace in Europe, probably in history, since the EU was formed post-WW2. Though we assume it will last forever, the EU is definitely not immune. There has already been clashes with Greece, with the EU trumping democracy: after electing an anti-austerity party (Syriza) in an election AND having a referendum which voted against an EU bailout package, Greece still signed up for its third bailout from the EU. The current ‘refugee crisis’ (which will only get bigger as time goes forward, it is far from being ‘solved’, and as the effects of climate change increase there will be many more refugees) has brought out huge tensions in the EU too. Perhaps the EU will collapse soon: definitely a possibility. Britain leaves, Greece and Portugal have financial issues, geopolitics has become more tense than it was anyway, there have been fractures with the refugee crisis with Germany breaking EU-law about refugees and having arguments with Eastern European countries. It’s been a long period of relative stability, and there’s no reason to be sure that will continue.

A different thing: the press. Most of the media companies have been campaigning for the Leave vote – the Sun, Daily Mail, Express, Telegraph, and so on. Most of this has been fraudulent and full of lies. The Remain campaign hasn’t been much better, with ‘project fear’ and vague assertions about economic and national security. This is as well as the issues I discussed above, with Corbyn and Sanders and Syria airstrikes. In the internet age, information is easily accessible. Media monopolies used to be due to printing and distribution networks: it has been a long time since a new national newspaper has been created. The traditional print media has had to shift online, but it’s been very difficult for them, along with other issues that media has been facing. I’ve long wondered if in the media versus Corbyn, the result might be that the media loses. If Remain wins – or if the general population realises the media lies in the Leave campaign – perhaps that will be part of the decline of traditional media companies.

*** 6. Conclusion ***

So, black swan events are what it’s all about, and there has been little discussion about what happens after the referendum.

Whichever way it goes, it will be different world after the referendum. There could be huge changes. If Leave wins, it might not be all bad: the Conservative party might collapse; the EU may be collapsing anyway, and we’ve got out before it gets even messier. Also, in the grand scheme of things, where we have huge crises of climate change and environmental destruction, nuclear weapons, huge geopolitical tensions, and the current system of neoliberal capitalism is quite clearly not working (inequality, both domestically and globally, plus aforementioned environmental destruction), perhaps the Leave vote isn’t the biggest issue.

Comments welcome!